Classic Stoics On Grief And Grieving (part 2)

Epictetus's views on grief as something bad and how we can escape from falling into it

The classic Stoic philosophers have quite a bit to tell us about the emotion of grief and the response of grieving losses in our lives. It is certainly a topic well worth exploring in detail, and rich enough to write a long and systematic essay on, something I might do in the future. For the time being, I am working on a series of shorter posts, each of which will examine aspects of Stoic thought on grief and grieving.

Some of these, like the first (and introductory) post I wrote a few weeks back, will range over multiple authors’ works. Others, like this one on Epictetus, will stick with the work of one main Stoic author that contribute to understanding grief in light of Stoicism. You can expect to see many more of these posts in the near future, as we bring to light all that the Stoics have to teach us about this practically inevitable experience of loss and the emotions that arise from it.

Why Look First At Epictetus On Grief?

There are several reasons I start here by examining what Epictetus says about grief and grieving first. One of these is a rather trivial reason which leads to a more important one. I am more or less following the order of the talk I gave, first at Wyoming Stoic Camp, and then later as an event in my YouTube channel. After outlining the Stoic theory of the emotions and where grief fits into it, I moved on specifically to Epictetus. Why discuss him first though?

When it comes to the Stoic thinkers whose works and thought we have available, Epictetus is one of the most important, arguably of equal importance to Seneca. So it makes sense that we would go through his works to see just what Epictetus has to contribute on this topic. As it turns out, in the works we have, the four books of his Discourses and the much shorter Enchiridion, he never provides a systematic account of grief and grieving, but he does have quite a bit to say about it at various points, sometimes directly, and sometimes by implication.

There was another reason I chose to go into Epictetus first. When you read across the body of available Stoic literature, you sometimes see interesting differences between how the different thinkers address particular topics. One prime example of this would be what Stoics ought to make of contemporary rival schools, particularly Epicureans, Skeptics, and Aristotelians, where there is clearly a lot of distance between how Epictetus and Seneca see these matters.

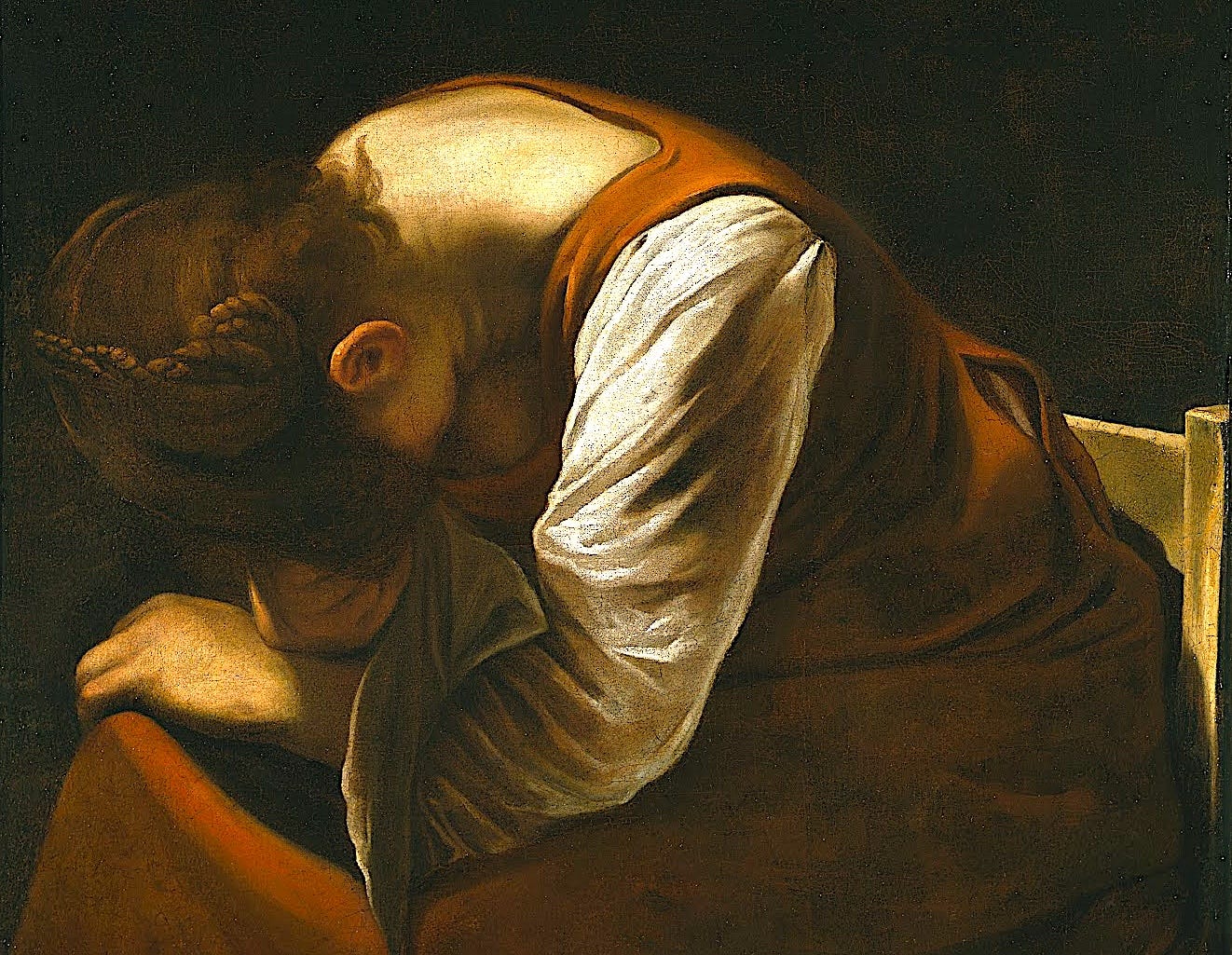

Grief and grieving are another of these matters. It strikes me that on these issues, Epictetus appears closer to the stereotype of the Stoic as someone who deliberately does not give way to what seem to be natural human emotions, and might even appear in some respects to be apathetic and heartless. This isn’t really the case, as we will see in just a bit. But looking at and contextualizing key passages of Epictetus that might fit this stereotype seems to me a useful way to proceed.

Selected Passages (And Some Hard Sayings)

Let’s start with a few of these passages that provide us with a picture of how the Stoic Epictetus regards grief and grieving. One of these runs:

[N]o good person laments (penthei) or sighs (stenazei) or groans (oimōzei) (Discourses 2.13)

It doesn’t seem that you can get any more categorical than this. Penthein is the verbal form of penthos, “grief”. So you could just as accurately translate this as “no good person grieves”. The other two verbs signify outward manifestations of grief.

Later on in the Discourses, Epictetus will speak of “words of bad omen” (dusphēma) Someone has just objected “those are words of bad omen” against his suggestion that when we are taking delight or joy in something, for example a child or friend, we ought to remind ourselves that they will die or depart. Epictetus turns that charge back around.

But do you call any things ill-omened except those which signify something bad for us? Cowardice is ill-omened, a mean spirit , grief (penthos), pain (lupē), shamelessness; these are words of ill-omen. And yet we ought not to hesitate to utter even these words, in order to guard against the things themselves. (Discourses 3.24)

Notice that among these “ill-omened” terms are both the specific emotion of grief itself and the broader emotional category of pain that grief is a emotion within.

The practice of deliberately reminding oneself that a child or friend might die or depart likely brings to mind one of the most (in)famous passages from the Enchiridion:

In every thing which pleases the soul (psukhagontōn), or supplies a want (khreia parekhontōn), or is loved (stergomenōn), remember to add this: what is the nature of each thing, beginning from the smallest?

If you love an earthen vessel, say it is an earthen vessel which you love; for when it has been broken, you will not be disturbed.

If you are kissing your child or wife, say that it is a human being whom you are kissing (kataphileis), for when the wife or child dies, you will not be disturbed (ou tarakhthēsē). (Enchiridion 3)

Many take this passage as definite proof that Stoics in general, and Epictetus in particular, advocate not allowing oneself to become attached to things and people vulnerable to death or destruction. Grief specifically and being troubled or upset more generally can be avoided if you just remind yourself what things actually are. If you choose not to practice this, and then end up feeling grief when your child or spouse dies on you, that’s on you. The bad experience of grief could have been avoided if you just didn’t get so invested in that relationship and person.

There is another passage from the same work that seems to make grieving a matter of external social forms and expectations.

When you see a person weeping in sorrow (klaiounta en penthei), either when a child goes abroad, or when the man has lost his property, take care that you are not carried away with the appearance (phantasia) that the person is suffering in external bad things. But straightway have this ready at hand: “it is not what has happened that afflicts this man, for it does not afflict another, but it is the opinion (dogma) about this thing which afflicts the man. So far as words go, do not be unwilling to show him sympathy (sumperiepheresthai), and even if it happens so, to lament with him (sunepistenaxai). But take care that you do not also lament internally (esōthen). (Enchiridion 16)

Since the other person isn’t a Stoic, they fall into common mistakes of assuming that external things that occur can actually be good or bad in a real sense, and of not realizing that it is their judgement or opinion that something is bad that makes it bad for them. They are affected or afflicted, and they feel a negative emotion like grief as a result. And you can even sympathize and lament with them. You just don’t want to allow their emotion to spread to you like a contagion.

One other passage is particularly worth mentioning to flesh out this brief portrayal of Epictetus as being against grief as a human emotion (and also counseling us to avoid and remove the sources of that emotion). Not only do we need to deal with the grief we may feel at the death or loss of other people. We need to also deal with grief we might be tempted to feel for ourselves. Epictetus asks:

Shall I not escape from the fear of death, but shall I die lamenting (penthōn) and trembling (tremōn)? Discourses 1.17

It is just as bad for us to grieve for the loss of our own lives, Epictetus suggests, as it is to grieve over the deaths of loved ones.

Clarifying Epictetus’ Account By Examining Assumptions

Given the passages just mentioned, considered entirely on their own, outside of the broader context of Epictetus’ works, it might be easy to conclude that he does represent the sterotypical “stoic”. He seemingly say that grief as an emotion is just bad, and something we can and should avoid feeling. The key would seem to be minimizing or even removing our attachments and expectations, not just to things going the way we want, but even those bearing on people we like, care for, or love. Other people who aren’t Stoics are going to fall into grief, and it’s all right for us to outwardly sympathize with and console them, even play-act at grieving with them. But we need to keep our inner selves pure and free of grief.

To be sure, some of this is true. As an emotion, the Stoic Epictetus does think grief is something bad for us to experience. And he does think that we don’t have to feel it. It is possible for us to not be affected in that negative way when someone connected to us dies, or we face what feels like an unfair or premature death threatening our own selves. But should the counsel to avoid grief lead us to insulating and isolating ourselves off from people who we have determinate close relationships with? From our parents and children, spouses and significant others, our friends and companions?

The answer is: Definitely not! Stoics think that integral to our rational nature is being social creatures, and over and over again they stress that this means being affectionate, caring, concerned, and loving towards them. That’s part of the “duties” or “appropriate actions” (kathēkonta in Greek, officia in Latin) that our very roles and relationships involve according to Epictetus (Enchiridion 30, Discourses 2.10)

Let’s put that response aside for the moment and consider another line of approach to the matter. Epictetus famously distinguishes three main fields or disciplines (topoi) of study for the would-be Stoic, and discusses these at multiple places in his works. Rather than canvassing all of the references to the three fields, let’s just focus on one particularly germane discussion.

There are three fields of study in which the person who is going to be fine and good (kalon kai agathon) needs to be trained (askēthēnai). The first has to do with desires and aversions (peri tas orexeis kai tas ekkliseis). . . . The second has to do with choice and refusal (peri tas hormas kai aphormas), and quite simply with duty (haplōs ho peri to kathēkon). . . . The third with the avoidance of error (anexapatēsian) and rashness (aneikaiotēta) in judgement, and in general about cases of assent (sunkatatheseis) (Discourses 3.2)

Which of these three disciplines have to do with the emotions? Primarily the first, since Epictetus tells us that it is “about the pathē”, which do arise out of desire and aversion. He goes on to say that this field of study deals with (among other emotional responses) instances of being upset (tarakhas), feeling grief (penthē), or lamenting (oimōgas). We should, however realize that the emotions are not exclusively the province of the second and third fields. What we do in terms of choice and action with the emotions we feel, i.e. the emotion’s expression, involves the second. And the third is also involved?

How so? The Stoic theory of emotion, which Epictetus would be well-familiar with and presuppose, holds that emotions involve complex judgements about matters, judgements which could be correct or incorrect, well-founded or not. Every emotion involves assenting to or assuming several things, perhaps without thinking much about them, but assent nonetheless.

We should think about what we assume or unthinkingly assent to in our interpretations of the passages from Epictetus above, which have to do with grief. Let’s say for the moment we agree with Epictetus that grief is something bad for us to feel. What then are the implications for us? What is required if we want to remove the sources of grief? This is where we can easily get things wrong.

Consider Enchiridion 3 again. The goal there is not to be disturbed or upset, and then when it comes to the possible death of one’s spouse or child, not to feel grief. What does Epictetus think you have to do in order to pull this off? You need to remind yourself of something you’re likely to lose sight of, that they are mortal beings, vulnerable to dying. That is their nature.

And why would you lose sight of this? Well, that has to do with desire and aversion. We’d like for them to live forever, even though this is a foolish thing to desire. We are averse to them dying, perhaps because we genuinely don’t want them to have to face death, or perhaps because we don’t want to be bereft of them. You could call this wishful thinking and a refusal to face the reality that we are all going to die sometime. That’s what we ought to call into question. Basically these are mistaken judgements. And those mistaken judgements feed into the grief we feel when our child or spouse dies (and perhaps feel even before they die).

To read Enchiridion 3 and to take from it the message that what Epictetus thinks we ought to do, if we want to insulate ourselves from falling into grief, would be to in any way keep people we are in relationships at a distance, to avoid or lessen feeling affection, care, or love for them, would be a great error. The persons themselves might be who we grieve over when they die, but they are not the sources of our grief. Nor are the good emotions, actions, choices, we exhibit towards them. Those aren’t what cause our feeling of grief.

In fact, built into the very passage is the fact that you do feel affection or love towards those people. Epictetus uses the term stergomenōn, which is connected to the “familial affection” (philostorgē, philostorgein) he discusses and praises as a good emotion one ought to feel at many points in his works. Notice that Epictetus doesn’t say anything remotely like: “You love those people, your spouse or kid? Well, when they die, you’re going to feel sad over their loss. So if you don’t want to feel sad like that, what you need to do is love them less, or ideally not at all.”

And why not? Because you ought to love them. There’s nothing incompatible between truly loving a person deeply involved in your life, realizing that they are mortal and could be taken from you at any time, and not having to feel grief when they die. Will that last bit happen with most people, even most Stoics? Well, probably not. But one can certainly feel less grief, not be completely overcome by it, if one does love other people but keep in mind that they are mortal, and that we live in a world that does not cater to our whims and wishes, however wholesome we might believe them to be.

One common mistake people make about grieving for lost loved ones, one that both Cicero and Seneca identify (which we will discuss in later installments), is thinking that if you don’t feel grief for someone you lost, you don’t or didn’t really love them. If you did love them, then you’d feel the loss, and that would take the form of the emotional response of grief. Epictetus doesn’t explicitly call this out as an erroneous line of reasoning (whether conscious or implicit) that many people buy into. But it is a point he could easily have made, given all the other things he tells us about love, vulnerability, and grief. What it comes down to is that people wrongly judge or assume that love and grief must necessarily be connected with each other.

There’s still plenty more about Epictetus’ views on grief and greiving to work though. Some bits of have been brought up already in this post. Other bits will require digging around further in his texts. But this is where we’ll leave off for the moment

Thank you! Loosing a partner is tough. Needed this to hear. I am a novice to Stoicism.

I'm glad you're tackling this over a number of pieces. It's one of the themes which even people who have some sympathy with Stoic views (let alone those who don't), routinely either misunderstand, misrepresent, or both. Looking forward to forthcoming parts.