Classic Stoics On Grief And Grieving (part 1)

where does grief fit into the Stoic theory of emotions?

One topic discussed by ancient thinkers who were either Stoics or deeply engaged with Stoicism is the emotion of grief caused by loss of loved ones. Their discussions bear upon grief over the deaths of friends and family members, and occasionally even touch on feeling grief over one’s own death. I’ve been reading about, reflecting upon, and occasionally writing about Stoic views on these matters for a while, and dealing with grief for a much longer time.

We buried my dad when I was just about to turn twelve. By the time I finished college, I’d lost both my paternal grandparents, my best friend, a girlfriend, and several cousins. My mother drowned in a river-rafting accident before I turned thirty. So I, and those close to me, have experienced their fair share of grief. While I can’t say that I’m in entire agreement with everything the Stoics have to say (and even among the Stoics, there isn’t always complete unanimity on every matter), I’ve found their works quite helpful.

I’ve been meaning to put together a set of posts systematically exploring what the Stoics have to teach us about grief and grieving. This, I’m happy to say, is the first of those. I’m not sure how many articles here it will take me to exhaust the topic, but I plan to keep working away at them until the series feels finished.

One good place for us to start, I think, is by looking at what Stoics have to say about grief as an emotion, by examining their views on the emotions in general. Some of this might be well known to some readers, but odds are will be new to many. This is particularly the case for those who have derived incorrect ideas about what Stoicism means and what Stoics think. For example, quite a few people mistakenly believe that Stoics disdain and attempt to repress the human emotions, which isn’t the case.

Unfortunately, we don’t possess the early Stoic treatises specifically focused on the emotions, for instance Zeno’s On The Emotions (peri pathōn) or his Ethics, Cleanthes’ works on more specific emotions like On Envy or On Love, Chrysippus’ On The Emotions, or Hecato’s work of the same name. What we do have, however, are later accounts that preserve and provide us with some of the early Stoic teachings on these matters. Quite a few of these accounts are not by Stoic authors but rather summarize what Stoic doctrines on these matters are. They include:

Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, particularly books 3 and 4

Arius Didymus’ Epitome of Stoic Ethics, specifically section 10

Diogenes’ Laertes’ Lives of the Philosophers, book 7, chapter 1, sections 110-116

Pseudo-Andronicus’s work On Affects (or On Emotions)

Drawing upon these works, there are four main interconnected teachings for us to examine. These are:

the distinction between good and bad emotional states

Stoic definitions of bad or problematic emotion

the Stoic fourfold classification of emotions

the emotion of grief specifically as a subdivision of pain

Let’s start at the start.

Good And Bad Emotional States

When it comes to affective states or emotions, Stoics distinguished between good emotional states and bad or problematic emotional states. The good ones are what they call the eupatheiai in Greek or constantiae in Latin. The broadest categories of these good states are what we typically translate in English as “wish” (rational desire, boulēsis in Greek), “caution” (rational fear, eulabeia), and “joy” (rational pleasure, kharis), but each of these encompasses a number of other more specific emotions.

The bad or problematic emotional states are what the Greek Stoics called the pathē, a term that in other philosophical systems simply mean emotions in general. In Latin, we see multiple terms used, including passiones and affectus. Some people might be put off at this point, in reading about Stoics viewing some emotional states as being bad (which is why I sometimes like to use that euphemism “problematic”).

What the Stoics understand by this badness is not so much that experiencing these emotions turns a person into a bad person, but rather that these emotional states are something bad for the person who feels them. They make that person’s life worse instead of better. Feeling those emotions is a sign and result of a person being badly off with respect not just to what they feel, what in the broadest senses they desire or are averse to, but also what they think, what they reason, what they judge. All emotions, good or bad, have cognitive as well as affective sides to them, for the Stoics (as well as other ancient virtue ethicists).

What is wrong with these bad or problematic emotions? Now we need to move on to our second main matter.

Stoic Definitions Of Emotions or Passions

From the texts mentioned just earlier, we get a number of definitions of emotion, many of which trace back to Zeno, the founder of the school. In his summary of Stoic doctrines in book 7, Diogenes Laertes tells us

passion or emotion is defined by Zeno as an irrational and unnatural (alogos kai paraphusin) movement in the soul, or as an impulse in excess (horme pleonazousa, 110)

Arius Didymus provides a very similar definition.

a passion is an impulse which is excessive (hormē pleonazousa), disobedient (apeithē) to the choosing reason, or an irrational motion of the soul contrary to nature. Also every agitation (ptoian) is a passion, and vice versa (10)

Notice the “excessive impulse” occurring in both definitions, the aspect of being irrational or disobedient to reason, and the reference to nature.

Arius also provides important clarification for what “irrational” and “contrary to nature” are intended to mean. Irrational means “disobedient to reason”, and contrary to nature means “something that occurs contrary to correct and natural reasoning”.

Cicero also references Zeno, telling us that:

Zeno defines pathē as agitation (commotio) of the soul alien from right reason (aversa a recta ratione) and contrary to nature (contra naturam, Tusculan Disputations 4.5)

Again, a very similar formulation, which gets some additional unpacking a bit earlier in that work, where Cicero tells us:

all disturbance (perturbatio) is a movement of the soul either destitute of (expers) reason, or contemptuous of (aspernans) reason, or disobedient to [non obediens] reason (Tusculan Disputations 3.10)

We now have a number of ways in which the bad emotions are “irrational”. Notice as well that Cicero uses a different term, “disturbance”, perturbatio. Yet earlier in the work, he expresses his preference for this term as the best way to translate the Greek term pathē, explicitly saying that one could call them “diseases” (morbos) but that disturbances is better (3.4).

Now that we understand what bad emotions or passions are for the Stoics, we can now break them down further, following their traditional schema.

The Stoic Fourfold Classifications Of Emotions

The Stoics developed a systematic approach to the emotions that placed them in four main categories, each of included a number of specific emotional states. Focusing on the cognitive dimension involved in all emotions allows the Stoics to delineate these four main types of emotion from each other not just on how they feel, or what sort of action they express or involve, but also even more importantly on the sort of judgements that are involved in each of them. So, what are the four main types?

Pleasure (hēdonē, laetitia). Arius defines this as “elation (eparisin) disobedient to reason, forming opinion a good is present” (10b). Diogenes “as irrational elation at getting what seems to be choiceworthy”. And Cicero tells us that it is “belief (opinio) of present good, and the subject of it thinks it right to feel enraptured (efferri, 4.7)

Pain or Distress (lupē, aegritudo). Arius tells us this is “contraction (sustole) of the soul disobedient to reason, forming opinion evil is present. Diogenes that it is “irrational mental contraction”. And Cicero, “belief of present evil, the subject of which thinks it right to feel depression and shrinking of soul.”

Desire (epithumia, libido). Arius says this is “desire (orexis) disobedient to reason, forming the opinion that good is approaching.” Diogenes calls it “irrational desire”. and Cicero “belief of prospective good, and the subject of this thinks it advantageous to possess it at once.”

Fear (phobos, metus). Arius calls this “avoidance (ekklisin) contrary to reason, forming an opinion that an evil is approaching. Diogenes says it is “expectation (prosdokia) of evil.” Cicero, that it is “belief of threatening evil, which seems to the subject of it insupportable.”

You notice that each of these kinds of emotion involves multiple judgements. There is a judgement that something is good or bad, and that it is present or not yet present (this itself is a complex judgement, composed of two simple judgements). And that judgement determines what kind of emotion it is, broadly speaking. It’s entirely possible, and often the case, that people making these judgements are actually wrong in doing so, thinking for example that something is good or bad when it is not. Then there is a judgement about the appropriateness of the response to the apparent good or evil, for example that it is right for a person to avoid something that they perceive as an evil, in fear.

We should note that the three good emotional states mentioned earlier correspond to three of these bad emotional states. There are rational versions of desire, fear, and pleasure. But, interestingly, for Stoics, there is no rational and good version of pain. And for our study of grief, that is particularly relevant, since that is the broad category of emotion that grief will fall into.

Getting Specific About Emotion(s): Where Grief Fits In.

As mentioned earlier, each of these main kinds of emotion gets broken down into specific emotions that fall within that particular classification. It is worth pointing out that the discussions we have of how this breakdown works vary from text to text. So when it comes to the broad emotional category of pain, for example, Diogenes Laertes distinguishes nine distinct specific emotions, Arius Didymus ten, Cicero fourteen, and Pseudo-Andronicus twenty-five.

Comparing the lists, you’ll notice a lot of overlap between them, but interestingly, the one specific emotion we are most interested in, grief (pothos in Greek) does not make it into Diogenes’ Laertes’ list at all. It shows up in Arius, Cicero, and Pseudo-Andronicus, however, and the latter two also single out additional emotions (really more expressions of emotion) relevant to grief and grieving. They also provide definitions or characterizations of grief.

Arius and Pseudo-Andronicus both provide the same definition: “Grief is pain at a premature death (epi thanatō aōrō)”. Cicero gives a similar definition: “Mourning (luctus) is distress arising from the untimely death (intertitu acerbo) of a beloved subject (carus).” One might wonder why these authors include the qualification “premature” or ‘untimely”, and that is an important clue. There’s a (inevitably mistaken) judgement involved on some level that the person should not have died, or at least not yet, not now.

Cicero also mentions sadness (maeror), a term that he uses often for grieving a loss, and defines it as “tearful distress” (aegritudo flebilis), as well as pain or grief (dolor), which is “torturing distress” (crucians). And then there is lamenting (lamentatio), which he defines entirely in terms of expression as “distress accompanied by wailing” (cum eiulata).

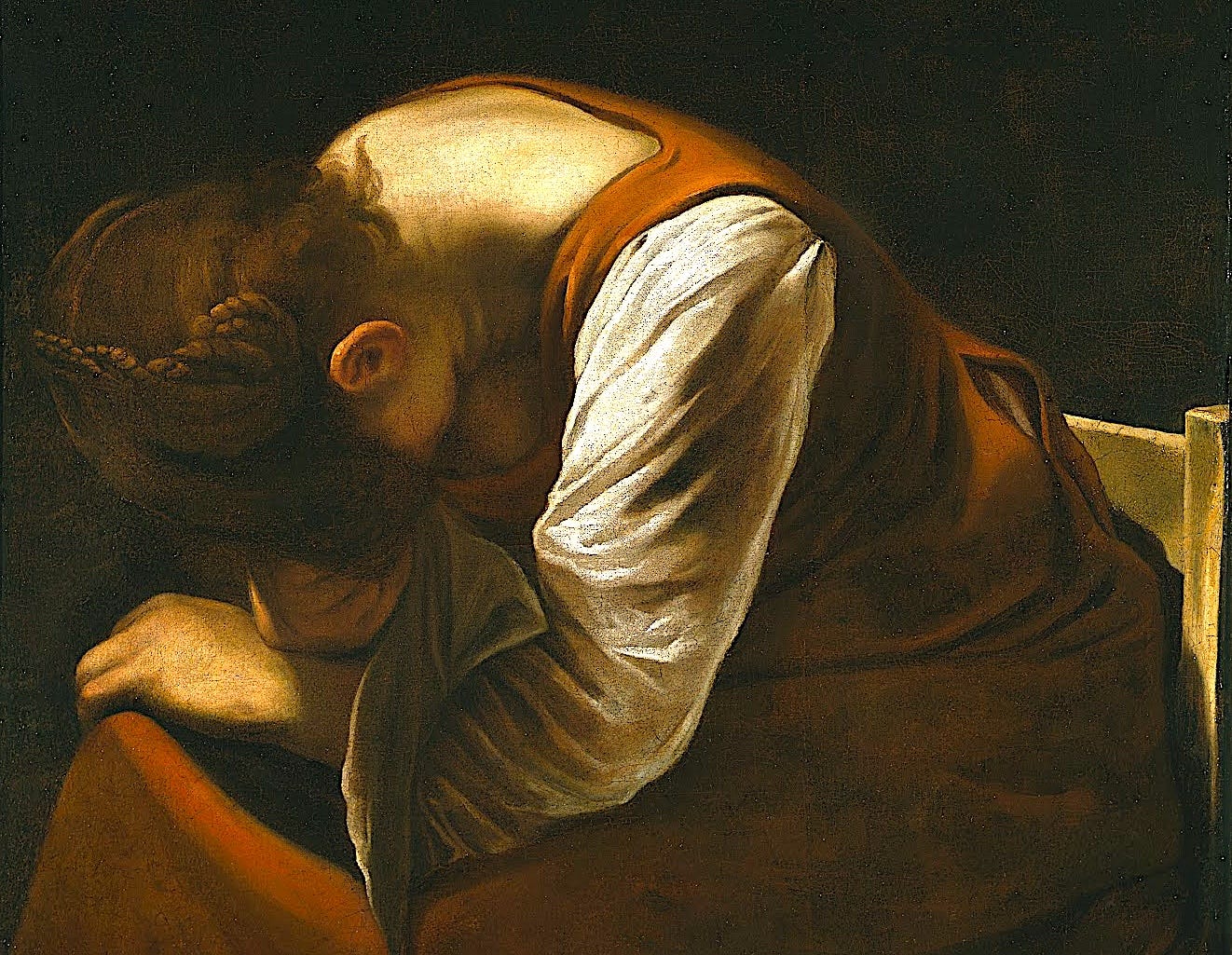

Pseudo-Andronicus mentions two emotional responses that would seem to correspond with lamentation. There is “wailing” (goos), “lamentation of someone laboring under vexation”, and “weeping (klausis) “the crying of someone who is vexed and bent over onto their hand.” He does also include “distress” (akhos), which is characterized in translation as “grief producing speechlessness”, but perhaps “grief” is better replaced by “distress” or “affliction” here.

So that’s where grief proper and several closely related emotional responses fit into the Stoic classification of the emotions. They are all instances of the broader category of pain or distress, and as such, they are all disturbances or passions in the bad sense.

One might make an immediate inference from this, that the Stoics thought grief was quite simply bad, and add to this another inference, that if one wants to be a Stoic, one should eliminate, conceal, resist, or repress grief when one experiences a loss. That’s actually not how Stoics approach this emotion, however, as we will see in the forthcoming parts of this essay.