What Epictetus Really Thinks Is In Our "Power" Or "Control"

The dichotomy of control is more complicated than many people think

(This piece was published earlier in my Medium blog, Practical Rationality. Medium eliminated free reads of articles behind the paywall, so I’m reprinting it here to make it publicly available)

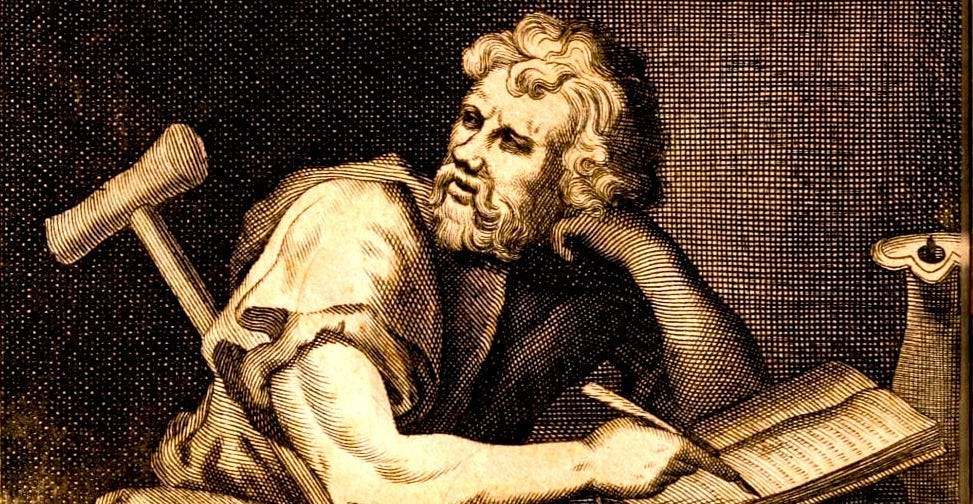

The distinction between what is “up to us” — “under our control”, “in our power,” or if you prefer, “our business” (ep’hēmin in Greek) — and what is not up to us (ouk ep’hēmin), eventually becomes a central doctrine of the Stoic school and tradition of philosophy. This particularly so in the thought of the late Stoic Epictetus, where the presently much-discussed “dichotomy of control” receives its definitive formulation.

The handbook, or Enchiridion, compiled by his student Arrian from the much longer Discourses (preserved and composed by Arrian as well), begins by invoking this very distinction:

Of things that exist, some are in our power and some are not in our power. Those that are in our power are conception, choice, desire, aversion, and in a word, those things that are our own doing. Those that are not under our control are the body, property or possessions, reputation, positions of authority, and in a word, such things that are not our own doing.

The Discourses themselves begin with a chapter titled “On what is in our power and what is not in our power.” There Epictetus doesn’t provide a similar listing, separating off one side from another. He does, however, introduce another key point about what does lie in our power.

We possess, as an integral part of what it means to be a human being, something that in that passage he calls the “rational faculty” (hē dunamis hē logikē), and at other points in his work, the “ruling faculty” (to hēgemonikon), and the “faculty of choice” (hē prohairesis). As a side note, the identity of these three is an interesting part of Epictetus’ psychology; for a recent treatment of it, you can watch this talk.

Whatever aspect we wish to understand this faculty through, in book 1, chapter 1 of the Discourses, Epictetus points out that unlike other faculties or capacities, it is reflexive — that is, it applies to itself, not only by being self-contemplating, but even by taking positions of value upon itself. It also, in some sense, calls the shots for all of the other faculties, capacities, or skills of the human being. It is the highest part of a human person, really the core of who one is. And, as he points out, it is what is most in our own power. He calls this a “faculty of choice and refusal, of desire and aversion” and the faculty that “makes use of “ or, if you prefer, “deals with,” what we typically translate as “appearances” or “external impressions,” phantasiai.

So, to start with, we have a distinction that is absolutely central to Epictetus’s Stoic philosophy, one that he returns to over and over again throughout the two works of his that we possess. Given that these are compilations of selections from his actual teaching and conversations, this means anyone who spent much time with Epictetus would have heard him invoke, apply, draw inferences from, and clarify this distinction many times.

In fact, “what is in our power” and “what is not in our power” are, as he mentions, among the “general conceptions” or “preconceptions” (proleipseis), akin to other conceptions like good and evil, justice and injustice, what is rational and what is irrational, duty and what is against duty.

There’s much more to be said about this sometimes confusing topic of preconceptions in Epictetus’s thought, but it suffices to say this: what is in our power and what is not, like these other conceptions, both play an absolutely central role in Epictetus’s Stoic ethics, and tend to be a distinction we human beings consistently get wrong.

Why This Distinction Matters So Much

By the time that we might encounter Stoic philosophy, decide to study it, and determine a need to apply it within our own lives, typically we have already developed some strongly rooted habits that apply to what is in our power and what is not in our power. Some of these even have to do with what sorts of matters we think fall on one side of the divide or the other.

When a person, for example, believes that their financial resources or their social status is a matter entirely or primarily within his or her control, Epictetus would consider that person to have an erroneous perspective on those things, even if that person’s experience seems up to that point to bear out his or her way of applying the distinction.

A bigger issue concerning the distinction, however, has to do with value and disvalue. The Stoics consistently — indeed even paradoxically — asserted that some things were good, some bad, and that the others, strictly speaking, were morally indifferent. In certain of the authors, it is virtue that is the sole good and vice that is the only genuine evil, so that other things that we typically consider good — wealth, health, fame, opportunities, comfort, pleasure, and the like — or generally consider bad — poverty, disease, pain, and so forth — are not really so. They are morally indifferent, neutral, neither good nor bad.

The Stoic position as a whole is, of course, more complex than that, distinguishing “preferred” and “rejected” indifferents, those that conduced to or contributed in some way to the good or to the bad — but again, I’m going to just mention that, and move on.

In Epictetus’ works, there’s significantly less talk about virtue and vice by comparison to those of other Stoics. Instead, he frames matters in terms of what is and what is not in our power, and more specifically in terms of what falls within the scope of the faculty of choice and what does not.

What is good or evil for a person is what falls on the side of what is in that person’s power, what falls within the scope of their faculty of choice. This is what they can do, or at least decide about. What is not in a person’s power, what does not fall within the scope of their faculty of choice (often because it is determined by someone else’s faculty of choice) is — again, strictly speaking — neither good nor bad. It is external, and as such indifferent, at least for that person (since it could also be good or bad for other persons).

That’s definitely not the way most people, or even most moral theories, regard matters. Insofar as that is the case, Epictetus would say that they’re mistaken. Worse, they thereby set themselves up for a lot of unnecessary trouble — getting upset, experiencing negative and excessive emotions — being “hindered,” as the Stoics put it.

So long as our views about what is outside of ourselves, external to our own faculty of choice or our ruling faculty, are that genuine good and bad reside out there, our desires and aversions, following naturally, even automatically, along the lines sketched out by our thoughts and opinions, will seek the good for us out there in external matters. And we will largely end up unsuccessful in getting what it is that we want and avoiding what it is we don’t want.

Stoicism proposes instead an ongoing discipline of deliberately withdrawing one’s desires and aversions from external matters and applying them to what lies within one’s own person. So, getting this distinction right — what is in our power and what is not — turns out to be integral to understanding and practicing Stoic philosophy as a way of life. And that seems simple enough when first expressed or explained:

Make this clear and straightforward distinction.

Apply the distinction along the lines Epictetus and other Stoics made it.

Follow it out consistently.

And then, at least in the range of things that you do have control over, your life will get a lot simpler and better.

Following that course won’t — or rather, it is very unlikely to — bring you riches or property, fame or prestige, positions of power, or even dinner invitations (a topic Epictetus mentions quite frequently!). It might have some positive effects upon bodily health, if you’ve behaving temperately in terms of eating, drinking, exercise, and the like, but that’s not at all the point to it.

Those things aren’t where the genuine good you’re seeking or the genuine evil you’re avoiding reside. Those lie within the person, strictly speaking in the faculty of choice that is the lasting core of the person. And we do indeed have a choice to make with that faculty: do we focus primarily on what lies within our power, on using it well and improving it, or do we allow ourselves to be drawn into becoming more and more distracted by all those things that are not in our power?

Understandable Objections and Irvine’s Trichotomy

Invariably, whenever I’ve presented Epictetus’ views to students, and proposed that they consider how adopting those views would affect the life they are currently living, their aspirations and goals, their present priorities, there’s an initial positive response. And then, the same objections arise. “Wait, he’s saying I have no control at all over my own body? But that’s clearly wrong! I can decide for myself whether I exercise or not, whether I do risky things with my body or not, how much (if at all) I drink, how much and what kind of foods I eat.”

Students are entirely right to bring up these sorts of objections, not least given how uncompromising Epictetus seems to be in insisting that the body is, strictly speaking, outside of our control.

Similar objections can be brought up (and usually are fairly quickly) about several of the other things that Epictetus asserts to lie outside of our control. Money is one of those. I can (and generally do) decide how I spend my money, for example whether I do so prudently or extravagantly. I do determine whether I look for remunerative work or not. And if I have a job that brings in some income, it does seem up to me whether I meet the requirements for keeping that job.

Social approval or status may seem a bit more difficult to affect or control through our own choices, at least if our goal is to have and enjoy more of these. But we can easily throw both of those away by engaging in behavior guaranteed to damage or destroy them.

Now, as I’ll discuss in the next section, Epictetus does address some of these sorts of matters quite reasonably in other parts of his Discourses. Before that, though, let’s look at a way in which one contemporary Stoic, William Irvine, deals with these sorts of objections, in his book, A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy. He notes:

[Epictetus] states that some things are up to us and some things aren’t up to us. The problem with this dichotomy is that the phrase “some things aren’t up to us” is ambiguous: It can be understood to mean either “There are some things over which we have no control at all” or to mean “There are things over which we don’t have complete control” (87).

Irvine suggests replacing the “dichotomy of control” with a “trichotomy,” in which there are:

things over which we have complete control

things over which we have some but not complete control

things over which we have no control at all (89).

This trichotomy is a reasonable enough suggestion for addressing the kinds of objections mentioned above. We don’t have complete control over our bodies, or our finances, or whether we have a job come next Friday. But we do seem to have some measure of control over them. At the very least by our choices, our actions, our commitments, we can — sometimes — create the right sorts of conditions for things to come out all right, or even better than that, in those areas of our lives.

Irvine goes further than this, however, expressing several doubts or qualms about quite a few of the things Epictetus asserts to lie completely within our control: opinions or assumptions, impulses, desires, aversions, and the like. With the exception of opinion — understood in a certain way — these all ought to fall within the category of “things over which we have some but not complete control” in Irvine’s reinterpretation.

In fact, what we do have entire control over, in his view, are “the goals we set for ourselves” (91), “our values” (92), meaning how we value things in relation to each other, or at all, and “opinions” insofar as these bear upon goals and values (92). Having qualities of character or not, which Irvine derives from Marcus Aurelius, rounds out this list of “things over which we have complete control” (92–3).

The category of things over which we have some but not complete control becomes centrally important when we apply this trichotomy. Instead of adopting a passive, detached, or indifferent attitude toward them (becoming “withdrawn underachievers”), we ought to be concerned with them, treat them as important and valuable, and exert our agency with respect to them. But, since they are not entirely within our control, we ought also to adopt a certain reserve as well. We should, in Irvine’s words, “internalize our goals we form with respect to them” (97), that is, what we aim to attain, achieve, or produce should be something within our control, not an external over which we don’t have control.

He uses the example of a kind of performance, a tennis match. The Stoic player does not control whether he or she wins or loses the match. The player does control whether he or she plays to the best of his or her ability, however, and if this is made into the goal — an internal goal, rather than an external one — whether this player is disappointed by his or her performance depends entirely upon that player. Analogously, we have the capacity to make only internal goals relevant for us when we’re dealing with those things that are only partly in our control.

Irvine does note: “In my studies of Epictetus and the other Stoics, I found little evidence that they advocate internalizing goals in the manner which I have described” (99). But, in his view, this approach of internalizing goals (along with the trichotomy of control) is plausibly how classical Stoics would have addressed the sorts of objections their doctrine is likely to — and often enough does — raise from non-Stoics.

A Fuller Response Derived from Epictetus’s Discourses

If we focus upon Epictetus’s Discourses rather than confining our attention primarily to the Enchiridion, we find something quite interesting. Although Epictetus does not articulate something precisely like Irvine’s trichotomy of control, he does make a number of remarks that indicate that the dichotomy of what is in our control and what is not possesses considerably more flexibility and sophistication than it appears to at first glance.

To start with, he provides a useful clarification in book 4, chapter 1:

What are the things that are another’s? The things that are not under our control [ha ouk estin ep’hēmin], whether to have or not to have, or to have with a certain quality [poion ekhein], or to have in a certain way [pōs ekhein].

He goes on to bring up familiar examples — the body, its parts, property or possessions (ktēsis) — precisely the sorts of matters that students express their understandable objections and misgivings about, and among the matters Irvine’s trichotomy is intended to address.

Notice that in this passage, Epictetus does not require the things that are not our own, that fall into the class of “out of or control”, to be entirely so. They fit into this class if we have no role in determining whether they exist or occur, or not — including whether we have them or not. But they also fit into this class if we are unable to determine whether they exist or occur with a certain quality, or in a certain way. One might rephrase this as a matter of features or aspects of those things lying beyond the scope of our control.

For example, you can set a beautiful table and centerpiece for a dinner party, you can exercise imperious rule over the kitchen fiefdom, and line up a wonderful set of guests — all things that with a bit of effort, some long-developed talents, and the right resources, it seems one can indeed control. And yet, a myriad little details remain outside of one’s control.

The centerpiece flowers begin drooping an hour in, unnoticed spots on the silverware come embarrassingly to light, a sauce goes wrong, due to one ingredient or another not being up to snuff… one could imagine all manner of mishaps, which can then lead to other ways in which the overall dinner party eludes one’s best efforts to control it through careful planning (and all of this is imagination on my part — I haven’t given a dinner party in over a decade!).

Epictetus provides many other important clarifications bearing upon this distinction of what is and what is not in our control. Perhaps the one of the widest scope is his repeated insistence that, although externals are indeed outside of our control, what we do with them, how we respond to them — what he calls their khrēsis, which we can translate literally as “use”, and more figuratively as “dealing with”.

This comes up in book 2, ch. 5 in the course of a discussion of how magnanimity and carefulness are compatible (closely connected with an earlier discussion in ch. 1 about confidence and caution). He starts out by noting “matters [hulai] are indifferent, but the use we make of them is not indifferent… to make a careful and skillful use of what has occurred, that is the task for me.” He adds, a bit later:

Are externals to be used carelessly? Not at all. For again, doing this is something bad for the faculty of choice, and is, with respect to that faculty, contrary to nature. Rather [externals] must be used carefully, because their use is not something indifferent, and at the same time with steadfastness and without being troubled, because the matter itself is something indifferent. For in what does make a difference, nobody can hinder or compel me. Success in those things in which I can be hindered or compelled is not in my control, nor is it good or bad — but the use [I make of them] is bad or good, and is under my control.

Epictetus uses two main examples to illustrate his point. One of these has to do with travel, in his time an often dangerous prospect. It is up to us to select the ship, to choose which crew to trust, and to decide when we will sail. But after all of this care has been exercised, we can still run into a storm. The other has to do with “playing ball” — and not just in the literal sense but one close to the metaphor we still use today, evidenced by the fact that Epictetus singles out Socrates at his trial as a person who knew how to play ball skillfully.

When we look at these passages — and there are many more that could be brought up — what we see is that the fundamental distinction Epictetus makes between what is in our power and what is not (or if you prefer the more contemporary jargon, the “dichotomy of control”) is something a bit more complex than one might assume.

It isn’t that the distinction isn’t a clear, well-argued, and in some respects strict one, but it is the case that many of the objections or other problems people would have with that distinction were already foreseen and addressed by Epictetus himself. When it comes to many of those things that, broadly speaking, from a Stoic perspective, are outside of our control and are morally indifferent, noting and acting upon this fact does not at all imply that one has absolutely no capacity to take part in determining these matters.

Epictetus does not elaborate a trichotomy of control in an explicit manner as Irvine does, but that distinction is clearly consonant with the ways in which he works through the dichotomy (or more strictly speaking, refines and properly applies the preconceptions of “what is in our control” and “what is not” to specific cases and particular matters).

The third, additional branch of Irvine’s trichotomy can be rolled back into Epictetus’s dichotomous distinction, as comparison of their two ball-playing examples shows (and similarly, the discussion of the skilled musician in book 2, ch. 13). That doesn’t mean, of course, that Irvine hasn’t done a valuable service to many modern-day practitioners of Stoicism; they’re far better off armed with his trichotomy, which they can then apply to understand matters better when confusions or objections arise for them about matters that seem to be at least partly in their control, for instance, the body.

But in my view, the would-be-Stoic, engaged in the necessary experiment of trying out Stoic doctrine, would be still better equipped by studying Epictetus’s own explanations and clarifications about the distinction. And for that, there is no substitute to working one’s way through his Discourses.

Where Greg indicates, “watch this talk”, provides a link to a very enlightening lecture on the material on this article.

Thank You Dr. Sadler.... This and your Talk on Askesis were great for getting this principle of self-control and what is really "Up to us " straight in my mind.