What Can Analytic and Continental Philosophers Learn From Each Other? (Part 4 of 5)

looking more closely at the Analytic-Continental divide

This is the fourth portion of the invited talk I gave at Virginia Commonwealth University to their Philosophy Club in 2016. The topic I was invited to address was the question in the title. You can watch or listen to the full talk in the videorecording. The talk itself runs nearly two hours, so I am breaking the transcript up into multiple parts, which I will post here sequentially. You can also read the already published first, second and third parts of the transcript of the talk.

Differences Between Analytic and Continental Philosophy

Now what about the “divide” then? What happens to it? Clearly there is some difference between analytic and continental philosophy. So what are the differences? Well there’s a difference in who is considered worth reading and thinking about, and how and what to read and think about them — what one’s motive is for for reading them, right? That’s part of it

There are clearly stylistic differences too. Does an article in a primarily analytic journal read like something that you’d find in a primarily continental journal? Not usually! Maybe they sneak something in every once in a while. I don’t know. I would have to do a survey. So there are stylistic differences. We can talk about different dialects or idioms perhaps in philosophical discourse.

And there’s geographical and departmental differences. Some places, it’s primarily analytics, some places, primarily continental. You always have to ask with continental “what kind of continental?” because they don’t always get along and agree with each other. But one thing I’d like to point out and stress again — there’s gaps and divides within analytic and continental philosophy themselves.

Past And Present Philosophy

There’s a gap between the present and the past. I think that if you were to ask 40 years ago about a canon of analytic philosophy — or even when I was in graduate school — if you were an analytic, if you were a student studying analytic philosophy, you actually read the canon of analytic philosophy. You may afterwards say “I’m not going to bother with these guys, because i’m just doing possible world stuff,” but you would read it, and maybe have to respond to it. I don’t think that’s necessarily the case these days, is it?

What about continental philosophy? There’s a huge gap between the present of continental philosophy and its past, I think, in some ways. And again, this is probably going to provoke some reaction from viewers. I think it was done in more serious ways in the past by some of the thinkers, than it’s being done by some of them today. There are also gaps in the present, and and we already talked about that with with continental philosophy. You know, marxists and psychoanalysts don’t always get along, just to pick a few things. Or marxists and phenomenologists, usually that’s a that’s a great one. Phenomenologists and anybody [else], often times.

What about an analytic philosophy? I don't mean things like having schools facing off against each other. Let me ask you this: does somebody who is working in ethics broadly construed in the analytic tradition, do they share the same, or even am overlapping reading list with somebody doing epistemology, or metaphysics?

Audience member: Yeah. Absolutely.

Do you think so? You think they all read the same articles?

Audience member: No, but there's a significant overlap. If you're thinking Venn diagrams there's lots of stuff different, but there's a core that they are all going to read.

I don't find that to be the case among a lot of my my younger analytic peers, but I probably know much less about that. My sample size is smaller, you know. I mean it looks to me as if there are growing divergences between different discourses within analytic philosophy. They're not actually reading each other. And sometimes the language, the same terminology doesn't mean the same thing going from discourse to discourse, so it always has to be defined

Ambiguity Of Terms In Analytic Philosophy

Audience member: that's absolutely right, you know, that the word “externalism” gets used different ways. Suppose “libertarianism” means one things when we're talking about free will and something else when you're talking about political philosophy. But why isn't that just a simple case of ambiguity? I mean, you know, we can do this all the time right? And anybody who works on free will and political philosophy, that's okay. When I'm doing political philosophy, I mean one thing by “libertarianism.” When you're doing free will, I mean something else.

And generally, they have to specify that at the beginning when they use the term right?I don't see that as just by itself being how these different fields are different. I think it's just a sign of how divergent they end up becoming.

Audience member: But it's not impediment to communication, right?

In theory you're right, yeah. I think that there's a lot of what's happening over here ends up just going its own way, and what's happening over here has ends up having very little connection with it other than they're using some sort of broadly analytic approach

Audience member: Can I ask a different question I probably should have asked an hour ago? So it's always seemed to me that the term “analytic” as it’s used in philosophy is ambiguous in a way that's very analogous to the way the word “classical” is used in music. So sometimes, if you're talking to serious musicians you know they'll they'll say well what I mean by “classical music” is a very distinctive style, you know typified by Mozart, that was prevalent in the late 18th century and very early 19th century in Vienna. And that's classical music right? And Mussorgsky is not a classical musician right? And neither is Rachmaninoff.

But there's this other much broader use where we what most of us mean by “classical music” is just sort of highbrow music. It includes everything from baroque to contemporary stuff, and I think so long as there's violins, there's some stuff like that the composer has a Russian or German name (well not necessarily!) Okay, so in philosophy you know there is this very somewhat narrowly construed notion of which is the analysis of concepts and languages — you know, we associate with Ryle and Austin and people like that. And that's a pretty well defined thing but reasonably — I mean I'm not saying we can give necessary and sufficient conditions — but we can all identify what counts as that. But there's this much broader sense.

You know you said this is an analytic department, and I think that's a fair characterization, but not in that narrow sense right? We're analytic in the way that Rachmaninoff is classical.

Yeah. I mean that style — let's call it “analytic” — it hasn't been a going concern for a long time.

Audience member: So what is this broader thing? Well look, as with classical music in the broad sense, you can't give precise identity conditions for it, but you can recognize it pretty well. And as you said, it has a lot to do with you know giving arguments, striving and often failing, but striving for clarity and for cogency. I don’t see. . . Does continental philosophy . . .what how does continental philosophy fit into that? Well I don't know. I mean some of it probably is that condition

Striving After Clarity

Oh yeah, that's a very good point. That's one of the things that people have been writing on. They point out, you know. Like in in terms of Husserl for example. You want some very detailed analyses of — not so much language, though he did do some some stuff with language. There there are some continental philosophers who've made (I was going to talk about this a bit later) a great effort to try to reach across the the gap or the divide, and frame things in ways that would aim for clarity, not always achieving it.

Habermas is a great example. I don't think Habermas is extraordinarily clear, but i think he's striving for that

Audience member: I agree, yeah.

About striving? Or about him?

Audience member: About striving, yeah. I think Habermas is. What my my thought about Habermas is that, insofar as I have been able to make sense of what he said, I think, yeah it makes perfect sense, and it's not all that interesting. You know, I mean once you pare it down and get to what he’s really saying, it turns out to be fairly trivial

Well, we could come up with many examples of that. So let's go back to this issue of the divide, and how it fits in.

History of Division

So let's say that there is some common core and approach to analytic philosophy. I think that you know at this point the divide has become more, as they say, sociological than rooted in some sort of essential difference. But that doesn't mean that it doesn't exist, or that it's going to go away. I think the biggest factor, as I'm going to talk about a bit later, is actually time, and the requirements that time would impose on this.

The history of the divide, you do have to admit, has involved a lot of unnecessary bashing, misrepresentations, even attempts to push out the other side from institutional spaces. One of the graduate schools that I applied to (when I was applying for graduate school back in 1994) actually sent me a letter back saying: “for the time being, we don't have a graduate program” And as it turned out they had a big fight, the way it sometimes happens, and the analytics were forced out by the continentals. And they lost so many faculty that, for the time being, they had to curtail accepting any new graduate students.

That sort of thing has been the case in the past i think, and I don't know whether this is really the case, but I think that it's much less common now. You know, that there is some some recognition of pluralism. I think that from a historical perspective, if we look at it as a genuine rivalry, it doesn't seem to be anything necessary to philosophy itself. It's not necessary for the present time, but there are some historically created gaps of understanding between analytic- and continental-formed philosophers.

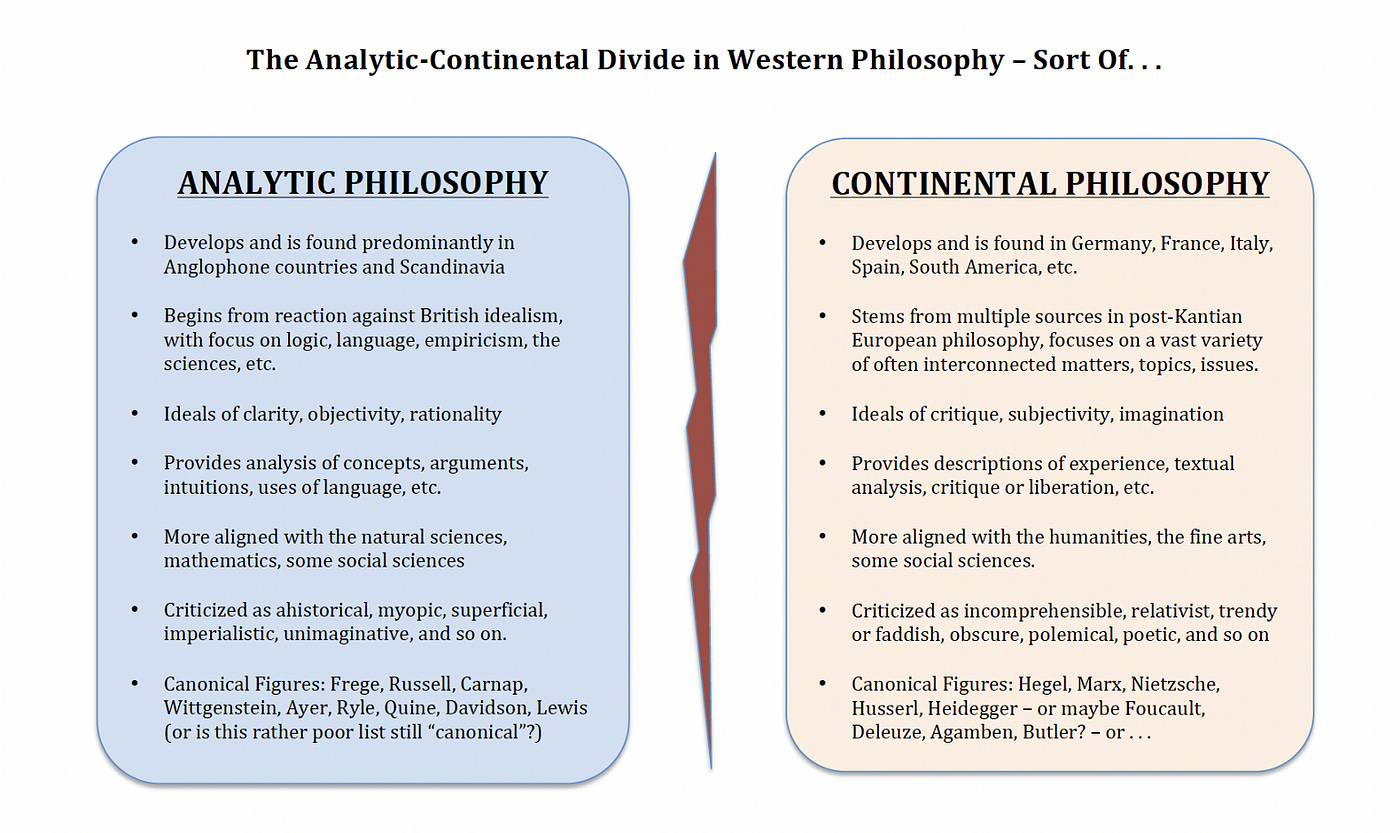

But the other thing I'd like to say too, is the notion of them sort of carving up the available space that gets put out there. You know in charts like like this.

I think that is very parochial. It ignores all the other stuff that that there is to do in philosophy, and that is getting done

Now granted, I would say American philosophy departments are — for the most part — either analytic or continentally oriented, although there are some ones that really do focus on classical American philosophy, or doing history of philosophy extraordinarily well.

Philosophers Bridging The Divide

So how might we view this divide then? I would say we should understand it as an important feature of the contemporary and likely future philosophical scene, but we want to broaden our horizons beyond it. We should look for models provided by thinkers like Habermas, for example, who try to make genuine efforts to to bridge this divide.

Somebody who I would point to in the history of analytic philosophy who did that, and I think did that quite well but not in a systematic way, was John Wisdom, who is kind of a minor figure but very, very interesting to read. He thought that he would take a look at what Sartre was writing and see if there was anything to it. He was interested in psychoanalysis as well. So you know you see somebody actually trying to do that. Paul Ricoeur — a great example — if you ever read The Rule of Metaphor, he’s explicitly engaging contemporary analytic philosophy of language.

And then I’d say there’s some interesting defectors as well, that are worth taking a look at. One of these is Richard Rorty, who starts out in analytic philosophy and then eventually does his own thing. They want to say that he’s in the American pragmatist tradition, but I don’t really know about that. I think he’s more doing his own thing informed by some things from analytic philosophy, some things from American pragmatism, and informed by some things from continental philosophy.

Another one is Alasdair MacIntyre. MacIntyre gets a start in analytic philosophy. He’s clearly not an analytic philosopher, but he’s clearly not a continental philosopher either. He’s doing something that he calls tradition-constituted rationality that — whether he gets his history of philosophy right or not (he’s been criticized by the Kierkegaard scholars about his Kierkegaard, and he’s been criticized by the Stoic scholars about his views on Stoicism), he is at least trying to think in a historical perspective.

What Can They Learn From Each Other

So let’s talk then about you know what i was supposed to talk about: What can analytic and continental philosophers learn from each other? There’s there’s a number of ways we can answer this for present-day philosophers. We can ask:

What can analytic philosophers learn from reading philosophers within the continental canon, and vice versa?

What can analytic philosophers learn from reading contemporary continental philosophers, including secondary literature or adaptations, and vice versa?

What can analytic philosophers learn by engaging in dialogue and discussion with continental philosophers? And what can continental philosophers learn by that?

And then what more general features characteristic of both could be learned?

And if you ask these questions, and you really try to answer them, there’s a presumption that something non-trivial is there to be learned from each other — that no one approach totally monopolizes what what counts as philosophy.

Maybe you find something that supplements your way of engaging in philosophy. Now it should be unsurprising, at this point, that my answers are going to suggest that some of the things that can be learned are not exclusive to analytic or continental philosophies, but to other approaches as well.

So general features, when I thought about this, the approach and the style of analytics — so analytic philosophy does in general get done with this guiding ideal of clear well-organized prose. Not just arguments, but clear well-organized prose, which I think is important. Providing explicitly worked-out arguments identifying what might be questionable assumptions or intuitions — could continental philosophers benefit by trying to adopt that idiom? I think they probably could.

I think some of them in doing so would discover that their research project turned out to be a failure. And so there’s a lot of engaging in obscurity, because it prevents one from having to say “there’s really not much here.” But it would be good as well for seeing what what really is there. At the very least, it’s a useful exercise to try to translate what one wants to say into a different style or idiom.

I think analytic philosophers, when they’re doing their work well, are quite selective in engagement with literature on their topic. Here’s one of what I consider to be a strength of analytic philosophy. When they make references to literature, like say footnoting, it’s usually relevant — and you know centrally relevant, not just tangentially relevant. That would also be useful for some continental philosophers to consider as a writing tip, right?

Now going the other way, some continental philosophers have a really robust engagement with thinkers and texts. And they aim at systematically understanding a philosophical perspective as they engage with it, not only in its own terms, but also in terms of its context, and structure, and relevance. And I think that can be useful for analytic philosophers to acquire as a skill — learning how to read text, not just in terms of dissociated claims and arguments. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with that, but you lose a lot by doing that.

Continental philosophers are also, you might say, more let’s just call it “adventurous” in their their choice of subject matter, what they’re willing to to draw upon. Although I think, if you look at content of more recent analytic philosophy, it’s harder to say that there’s there’s huge areas of human experience that are being left out. There’s so much work being done, but I think that looking at some of the examples could be could be useful for them.

Descartes, Travel, and Open-mindedness

I think both sides genuinely engaging each other helps to overcome a kind of, not closed-mindedness, but having blinders on, only seeing a very small portion of philosophy — an assumption that only one mode is is legitimate.

I actually would like to use a sort of an analogy to what Descartes says in his Discourse on Method. He suggests that travel is a really great idea. He had been a fan of the gap year, right? (the term that people use these days for the year that you’re not in school). And the reason he was really a fan of that, other than the fact that he had enough money to travel I think, is that he said that by watching people, you get to see how they engage in reasoning about their world. You get to see a whole bunch of other perspectives in action. And he thought that was a good thing. He thought you couldn’t do that so much from books (I think he’s probably wrong about that).

I think looking at how other people do philosophy could could be quite quite useful, and it breaks us free from a kind of conformity that that can be restrictive at times. So that could be a value that’s centrally involved in philosophy. I know it has been in the past. You know we talk as if — when we’re introducing it to undergraduates — as if that’s what philosophy does. So that could be good.

Reading Canonical Thinkers and Works

What about reading each other’s canonical figures? Now what are recognized as classic texts and important thinkers are usually worth reading, at least in my experience, for both the continental figures and analytic figures — but then again, I really enjoy reading philosophical texts. What can you do through that? You can get introduced to alternative philosophical perspectives and themes — ideas that some really intelligent people took seriously and found worth worth thinking through.

It also saves a bit of time from reinventing wheels. This is this is one of my complaints as I engage sometimes with colleagues doing things like virtue epistemology, which is primarily an analytic concern. You know they’ll do a lot of work, and then you’ll say: Yeah Aristotle already did that. Now we’re not talking about Aristotle, but continental philosophy. There’s some things I think, where it could be good to get ideas from continental thinkers

This is what Ricoeur recognized in The Rule of Metaphor. Sometimes the analytics are way ahead of the continentals on some important things, like how to understand metaphor. You can also understand or ascertain limitations or failures in those texts for yourself, rather than relying on secondary sources. If you want to know whether Hegel is indecipherable, read Hegel and then you know! It won’t take long before you’re getting that impression (I’m saying this as somebody who likes Hegel). If you want to see whether Heidegger is really on to something or not, you’ve probably got to read some Heidegger — and actually read it! Not just sort of skim through it, but see what’s there. You can see where the the problem of time is starting to raise its head though, right?

What about contemporary literature? I think you can say a lot of the same things about contemporary literature. The problem is there’s too much of it! There’s way more being churned out, and it’s tougher to see what in it is classic, because every book jacket says that this is the best text ever that that came out. So it’s hard to say exactly where you would go for for guidance on that. We do have to admit philosophy can be a little bit fad- or fashion-driven at times. So that can be an issue.

And what about dialogue, or collaboration? I think it’s useful to learn who matters to one’s interlocutors and why what value they have. What do they see in them?

And then, learning how to speak. It’s sort of like learning how to speak a different dialect, or perhaps even a different language in our discipline now, I think. Here’s where I’m going to put in my own two cents. Much of what’s particularly valuable that either side can learn from each other is something they can learn from other main ways of doing philosophy as well.

If you want clear exposition focused on setting out critically analyzing arguments, analytic philosophy doesn’t have a lock on that. All you got to do is read Thomists. Some of them were real experts in that, some of them not so much. You can also find this in a lot of historically-focused work.

If you want to see a focus on broader historical or social contexts, you might get that better from historical approaches than from contemporary continental philosophy. There are a lot of people out there who do work on historical figures, who are taking them very seriously.

People who are Aristotle scholars are writing on Aristotle because they think there’s something really there, and they read the whole corpus, not just portions of it. You’re not going to find a lot of — well you you will find one person I can think of, Agamben takes Aristotle seriously — but not too many others among continental thinkers. Learning how to read classic works of authors — not only pre-19th or 20th century, but even those authors who are considered to be analytic or continental thinkers — that’s something else that I think historians of philosophy are are good at.

That’s the end of the fourth portion of my talk. I hope you found it interesting, informative, and thought-provoking.

Gregory Sadler is the president of ReasonIO, a speaker, writer, and producer of popular YouTube videos on philosophy. He is co-host of the radio show Wisdom for Life, and producer of the Sadler’s Lectures podcast. You can request short personalized videos at his Cameo page. If you’d like to take online classes with him, check out the Study With Sadler Academy.