(an earlier version of this was published in my Medium)

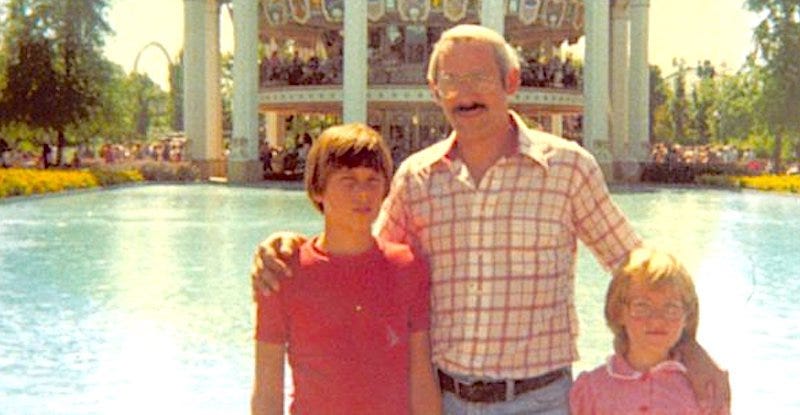

I lucked out in life, all things considered. My parents, Anton and Monique Sadler adopted me when I was just days old. After getting married in 1967, and unsuccessfully trying to have a child on their own, they went through two years of screening, and engaged in who knows how much preparation before I was even born. My mom had attended DePaul University, intending to become a French teacher, but then dropped out to marry my dad who was attending University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he did a degree in accounting, passed the CPA exam, and then went on to law school (where he was enrolled when I was adopted).

Not that long before he finished law school in 1973, they adopted my little sister (from different biological parents). He got a job with a rapidly expanding law firm, Touche-Ross, and we moved to the Milwaukee area until he and my mother had a house built out in a slowly developing subdivision out in the country just north of the village of Wales. We moved in near the end of 1974, I think, and that is where we lived until my dad died during the summer of 1982.

His mother died in 1977, and shortly afterwards we took in his father, a retired, hardcore alcoholic businessman to live with us. So for five year, it was the five of us together in our house, along with our dog Lady we raised from a puppy. And we had a solidly good life together as a family until my dad died.

What I’ve written here isn’t particularly well-organized, just some of my reflections about our life together, the kind of person he was, and our loss in his death. Perhaps if I’d written it on different days, different stories, events, memories would have come to mind.

From Wisconsin to Houston and Back Again

As a tax attorney, my dad was a hard and diligent worker. He had an hour’s commute in to work and then back out by us. During tax season, he would sometimes leave before we woke and come home after we were asleep, so that we would only see him on the weekends. He flew to Kansas City more or less monthly while he worked for Touche-Ross.

Wanting to have more time with us, at one point he left that firm and became the chief accountant at a firm in Waukesha, much closer to our house. I won’t name the company, since they still exist, but I can tell you that eventually he left them and went back to Touche-Ross because he figured out that the company was “cooking the books” and he refused to cosign and collaborate in the fraud. They took him back, but imposed a condition that would have radically changed the life of our family. My dad was assigned the task of opening up a new branch office for Touche-Ross down in Houston, Texas.

He was down there in spring of 1982 working through the many details involved in that task when he got sick. Seriously, life-threateningly ill. They diagnosed him first with pneumonia, then Legionnaires disease, and then basically gave up down there. My mom had him transported up by us to the hospital in Waukesha. Again, the doctors couldn’t determine for certain what was wrong. Over-confident diagnoses, failed treatments, and blustering refusals to admit they didn’t have a clue — while my dad’s condition worsened — determined my mom’s resolve to fly my dad up to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Three months later, after heroic attempts, he died.

We had been preparing that entire winter and spring to move down to Houston after the school year ended. My parents had researched all sorts of factors. Houses we might move into, the local school districts, where my sister and I might play soccer, even where we would dock the boat we had recently upgraded to. All of that just got postponed at first when my dad got sick. Then as he got worse and worse, we forgot about the move. We just wanted him to heal, recover, and then at the end, to live.

For a few years after he died, we would imagine what our lives together might have been like, as a family transplanted from Wisconsin down to the burgeoning city of Houston and the culture of Texas. At a certain point years later I realized that our continued life — remaining in our old house, my mom now back to work full time, the ruined wreck of my grandpa still living with us, all of us dealing (or not) with our grief — had diverged so much from a timeline in which my dad survived and we moved as an intact family together down to Texas, that there was no longer any real comparison possible. We had all become people too different from those imaginary ones.

I Lose The Sound Of His Voice

There were a lot of traces left of my dad, at least for a while. My mom didn’t get rid of his clothes, and as I got older, at least for a while, I grew into and wore some of them. His leather cowboy hat, his long leather jacket, his workboots. I took those and wore them until I outgrew them. I even kept a few of his ties, even though they were on the short side for me, and wore them for various work, until decades later I passed them down to my cousin, who was closer to my dad in height. He left behind a large and eclectic record collection, a small library of books, fancy beer steins he’d accumulated over time, and his tools. I tried to make use of all of those as best I could.

He also left behind a large and well-stocked tackle-box full of lures suited to fishing for everything from bass, perch, panfish all the way to northern pike and muskies. Along with them, there were the two beautiful enameled bait-casting rods and reels that we used on our frequent fishing excursions. My dad had an older half-brother who had a terrible childhood after my grandfather divorced his mother, essentially abandoning him. He was a jealous sort, and while there for my dad’s funeral, he quietly stole all of my dad’s fishing equipment.

One other object that my dad left behind when he died was a single cassette tape that had his voice on it. It wasn’t something that he had recorded for posterity. At this late date, I can’t even remember what was on it, other than him speaking, and that only for a few minutes. I found it among a number of other tapes in the stereo cabinet that held the high-end setup he had researched and bought a few years earlier.

For several years, I was able to remember the sound of my dad’s voice, and then my recall began to waver and fade. When I realized that I was losing that aspect of him, I began to listen from time to time to that tape, sometimes on my own and sometimes with my sister. Cassette tapes, especially the cheap ones you could buy in bulk back then, weren’t made to last, and eventually it began to stretch, which affected the sound and presaged what would inevitably happen.

The tape got caught, pulled out of its case, and crumpled up — but didn’t break — the first time. I wound it back up, and we got a few more plays out of it before the time it broke beyond any repair.

And then it was gone for good, the sound of my dad’s voice. Gone from my own memory. Gone from the physical recording. Gone beyond any means of recovery. I do remember things he said, the words, the ideas, even the feelings that went with them at a particular time and place. But the sound itself has faded into the past, never to be heard again.

A Man Who Made Time For Us

My dad was clearly a man who wanted to be many things in his life. He played football in high school and apparently was a promising athlete until an injury damaged his knee so badly he had to walk with a cane for years. As I mentioned before he went on to college, studying accounting and law, but he also read widely in history, literature, psychology, and political theory.

He was a lover of a music, ranging from jazz to bluegrass, from folk music to rock and roll. We went to Summerfest here in Milwaukee every year together. He coached my sister’s soccer team. He kept up with his friends, colleagues, and classmates. We visited and stayed with them, and them with us.

He spent a lot of hours engaged in work. I remember seeing him on weekends typing into his adding machine on our dining room table, as he did our finances or finished up work he had brought home from the office. He worked around the house and the yard as well. We planted a big garden every year. He bought and laid sod to turn out dirt yard into a real lawn. He bought, hauled, split, and stacked wood for our fireplace. He landscaped our yard over years, in stages. He cooked and grilled. I still remember pancakes on weekend mornings, and ribs and steak from the Weber grill on the deck he built with some help from our neighbors.

For someone who worked as much as he did and took time for relaxing, it is remarkable he found so much time for us kids and my mom, and for our huge family on her side. Even today, thinking back, I have no idea how he did it. He saved for years to buy a boat, a 18-foot tri-hull we christened the “Green Arrow”. We took it out on weekends to nearby Lake Nagawicka. If all four of us went out, we swam, picnicked, water-skied, tubed, and occasionally fished. The same went for the river trips we took, where we camped along the banks. If it was just my dad and I — which was the case many Saturday mornings — it was all fishing.

For a while, my mom worked part-time at J.C. Penny’s out at Brookfield Square, selling women’s clothes on the weekends. My dad would sometimes drive us out there while she was on her shift. We would pop in and say hello, get ice-cream, grab a meal, check out the various stores, and sometimes catch a movie, then go back home. Those evenings, he would usually make dinner as well.

When it wasn’t tax season, and while he was working at the Waukesha firm, we’d greet him when he came home. My sister and I would try to tackle him in the family room, and he would play-wrestle with the two of us. Sometimes, he would have stopped and picked up a Kit-Kat bar, which he would give the two of us to share. There wasn’t any “leave your father alone, kids!” from my mom, as there was in other families on our street when their parents came home from work, and wanted just to decompress on their own before dinner. Our dad genuinely looked forward to coming home and our time together.

One anecdote perhaps stands out for me. In 5th grade, I started reading Lloyd Alexander’s five-volume Chronicles of Prydain, captivated by the narrative and the characters. By the summer before 6th grade, I’d got my hands on all the books and reread them many times. I started writing a play in which people from our world stumbled through a gate into Prydain, encountered some of the characters, and of course fought battles against evil, particularly against Arwan, lord of death.

My dad found me working on it, read it, and told me to complete it. Once I had, he met with our drama teacher and convinced her that the 6th grade should put on the play. And indeed we did, with two casts doing the entire play one after the other. He got off work early and drove out to my school to watch the performances. (You can watch a video about that story here).

Missing Him As An Adult

Growing up without a father is a tough but unfortunately common situation. Witnessing what happened with many of my classmates and friends in the 1980s, when divorce split up so many of their families, I would compare my situation to theirs. Sometimes their dads just split, took off for parts unknown, with little to no contact other than the odd letter, phone call, or visit. Some settled into the every-other-weekend and half-the-holidays routine.

Quite a few of their dads began dating, occasionally beginning a new family that the older kids would find themselves passed over for. I remember thinking to myself that although our situation was bad in many ways, and that I’d never get to spend time with my dad again, there were at least two consolations.

One of these was that to the end, he loved us kids and our mom, his wife. I was a kid who questioned a lot in my childhood — so much that it drove some my teachers to distraction — but there was never a question for me that he loved us, cared for us, liked us as people, took an interest in our lives, feelings, thoughts, and development.

The other was that he didn’t choose to leave us. In fact the opposite. He struggled for months against whatever illness it was that progressively ravaged his body. He and my mother, consulting together, said yes to every procedure, every attempt of the doctors to determine what was wrong with his body, every effort to heal him. If he could have stayed with us, he would have.

His death still made for rough times. I remember starting seventh grade, and the oblivious teacher having us all go around and say what we did over our summer. What do you say in a situation like that? Grief wasn’t something you readily expressed back then, especially if you were a boy. I’d been advised by a number of well-meaning relatives and my dad’s friends at the funeral: “you’re the man of the house now”. And pretty much zero guidance about what that was supposed to mean. None of us processed our grief well — me, my sister who was just 9 when my dad died, my mother a 36-year-old widow, or my grandfather who buried his wife and his son in the space of 5 years.

I might have gotten in trouble as a teenager anyways, death or no death, but carrying the grief over the loss, adjusting to life in his permanent absence, and not having the sort of man my dad was to show me a good model of masculinity, I didn’t do particularly well.

I was driven to become a tough guy, started getting into a lot of conflicts and fights, and at one point was taken to the local juvenile detention center, temporarily became a ward of the court, and spent several months in-patient for psychiatric care. The first time I was invited to an actual support group for those grieving losses in their families was after that, in senior year of high school. There’s a lot more to be said about all that, but I’ll reserve that for some other time.

Suffice it to say that I got through those teenage years, having to learn difficult and painful lessons along the way. I would have almost certainly benefitted from my dad’s presence, counsel, humor, and care as I moved into adulthood, going off to college and graduate school, working a number of jobs along the way, going from one relationship to another until eventually marrying, having children, divorcing, then finding my “the one” and marrying her later in life.

There is so much that, as a grown man, I would have liked to talked with him about, shared with him, got his take on. Of course, if he were to suddenly come back from the grave today, he’d be lost for a while in a world that has so drastically changed, but after getting over his culture shock, I expect we would get to know each other in ways rooted in our past decades ago, but now as one adult conversing with another.

As I reflect upon the fact that four decades have passed since my dad died, I find there is so much more that I could write. Perhaps I’ll do that in some additional posts down the line. For the present, I feel that I’ve said enough about Tony Sadler. I still miss him, as a man now 18 years older than he ever got to be.

Your writing about your Dad really touched me, Gregory. I sure am looking forward to more of your writings

It really is the ultimate privilege, isn't it? Belonging to that cohort of people born (metaphorically in your case) to parents who did the best for us they could for us. I'm happy to be thus privileged, if not materially so.