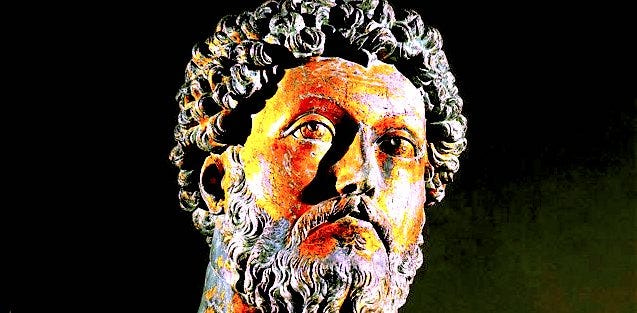

Marcus Aurelius’ Advice For Taming Our Anger

nine. . . no ten. . . no twelve gifts from the Muses, Apollo, and Aurelius himself

One of my favorite sets of passages from Marcus Aurelius’ book, the Meditations occurs in book 11, chapter 18. For those who have read that great work of Stoic philosophy, written by the Roman emperor to himself, you’ll recall it as a numbered listing of points or “headings” (kephalaiōn) Marcus reminds himself of, portraying these considerations to himself as being like “gifts from the Muses”.

He doesn’t remain content with setting down that nine, however, and adds one more point, attributing it to Apollo, bringing the total of numbered points to ten. He also inserts a few other reminders of his own between the nine and the tenth. Each of those additional practical insights bear upon the emotion of anger, as do — either explicitly or indirectly — all of the other points numbered in the nine or ten.

Commemorating the 1,900 year anniversary of Marcus Aurelius’ birth four years back, the Chicago branch of the New Acropolis invited me to give a short talk about Marcus to their membership, and I decided to place the focus on a topic in Stoic philosophy that I’ve found particularly helpful — understanding, managing, and lessening the emotion of anger. If you’d like to watch or listen to the talk, you can do so here.

Marcus’s Meditations have a lot to teach us about anger. In fact, as I mention at the start of the talk, in the very first line of the work — in book 1, focused entirely on gratitude — Marcus mentions anger, noting that his grandfather Verus not only was of excellent character (kaloēthēs) but also was good-tempered (aorgiston), literally the sort of person who would get angry rarely or not at all. The book 11, chapter 18 listing of points also draws a number of Marcus’ teachings and reminders about anger together

Outlining Marcus’ Twelve Points

How do we wind up with this number twelve? Marcus explicitly delineates nine points, one right after another, and then adds a tenth at the end, doesn’t he? That’s quite true.

But as we’ve pointed out, Marcus sandwiches some of his own observations in between the nine gifts from the Muses and the extra tenth one from Apollo. Different interpreters might parse these out differently, but in my view, there are two main points and practices that Marcus adds in there

one having to do with anger and selfishness

the other with anger, “manliness”, and real strength.

So adding these two additional ones, we have a total of twelve key points set out in chapter 18.

As a side note: Why didn’t Marcus go back through and straighten out his numbering properly? Or shift those additional points of his own to fall after the one labeled “tenth”? Who knows? He was writing to himself, after all, not to all of us readers in the 21st century. If the lack of complete ordering gets to you, and even provokes some irritation on your part — without Marcus intending this — that might have a useful function of making you think about why you’re edging down (even if just a little) that path towards feeling anger. In a short passage that can definitely help you dig into and deal with your anger — how funny is that?

Several of the points enumerated in Meditations book 11, chapter 18 bear directly on anger, and mention it explicitly.

Point 6 uses a verb (aganaktein), translated as “losing temper”, “getting irritated”, being “indignant”, and suggests a remedy.

Point 7 speaks specifically about anger (orgē) resulting from viewing things as bad when they actually aren’t.

Point 8 centers on instances of getting angry, and expressing or acting upon anger (orgai), and the pains in a broad sense that follow as a consequence.

Point 9 discusses the opposite of anger, being kindly or gentle (eumenes) with other people, approaching them calmly (praōs), that is without anger.

The rest of the numbered points don’t use explicit “anger-language”, but each of them implicitly — with inferences that are easy to draw — applies to the emotion of anger

Point 1 reminds us of our relatedness and responsibility to others.

Point 2 notes that people are compelled or necessitated by the beliefs (dogmata) they hold.

Point 3 adds to this this that people who do wrong do so unwillingly and out of ignorance (and that if they do right, we have nothing to complain about).

Point 4 turns the focus on us, noting that we do wrong actions as well, and that if we don’t do the same as the others, it’s still a possibility for us.

Point 5 is that we can’t be sure, in many cases, that people are actually doing the wrong thing.

Point 10 asserts that it is crazy to expect that bad people won’t act badly, but that one is still responsible for protecting others (as best one can) from bad people.

When we assemble all of these points together, as Marcus does in this chapter of the Meditations, they provide a powerful tool, composed of interconnected and mutually supporting Stoic insights and practices, that we can use to develop a better understanding of our own anger. Reading through these passages, reflecting upon them, applying them at appropriate points in our daily life, to unpleasant events and experiences, within the scope of our many relationships — over time, that will gradually make us less liable to anger, and better able to curb it when we notice it rising up within us.

We can also get a lot of mileage out of deeper consideration of each of the twelve individual points. In this article, I am going to focus on Marcus’ own two additional points, and then in two follow-up articles, I’ll go through and unpack the numbered points (one on those explicitly discussing anger, and the other of those implicitly applying to anger).

Anger And Selfishness

Marcus draws a connection between two different modes of going wrong in our lives and our relationships.

And along with not getting angry at others, try not to pander or flatter people either. Both are forms of selfishness; both of them will do harm.

Marcus literally tells us to be on our guard against both of these common types of comportment. But getting angry or acting upon anger (orgizesthai) would seem to be quite different from “pandering” or “flattering” (kolakeuein) — or to use more contemporary language, “sucking up” or “people-pleasing” — wouldn’t it? When we get angry, aren’t we asserting our rights or defending ourselves from insult or injury, priming ourselves to retaliate against another, to impose some suffering on them. Doesn’t that harshness and aggressiveness seem to reside almost at the opposite end of a spectrum from the softness, the suavity, the “niceness” of the flatterer?

Marcus singles out two things anger and flattery have in common with each other. And if you think about it, the second really follows from the first. What we can translate as “selfishness” has a somewhat wider range of meaning. The Greek term that Marcus uses is “akoinōtēta”, referring to a lack of koinōnia, sharing or community with others. So this means being “self-centered”, focused on one’s own individual goods, desires, perspectives at the expense of those of other people, those involved in a solid or fair relationship, and those of the larger community of which one is a member.

Flattery seems other-centered rather than self-centered — after all the flatterer is saying nice things to another person in order to make them feel good. But in a way it is even more self-centered, turning praise of others, giving them attention, treating them as if they matter into a mere means to the end of getting what one really wants. It is inevitably manipulative, false-faced, and there were good reasons why being a “flatterer” was both despised but also demanded (generally not by the same people) in the ancient world.

Anger also shows itself to be self-centered in a variety of ways, even when it might justify itself as a way or protecting vulnerable others who one cares for or identifies with, for example when angrily standing up for one’s spouse, children, parents, siblings, or other relatives. Anger can mislead us into pretending that what we do under its influence is really furthering the greater good. Just for one example, back in my angrier days, I would justify aggressively honking my horn and flipping the middle finger to people I considered bad or selfish drivers by saying that I was doing my part by giving them a message. The emotion of anger can prove quite seductive to what the Stoics call the “rational faculty” or the “ruling part” of ourselves, convincing us that what we are thinking, saying, and doing is reasonable and justified.

At other points in the Meditations, Marcus calls attention to how anger — along with other emotions and actions — tends to separate us off from other human beings, the larger cosmos, and even from other parts of ourselves. In book 2, chapter 16, he tells us that when a person is angry and trying to injure another person, that person’s soul does violence to itself, and separates itself off from the rest of the universe, like a tumor. In book 11, chapter 20, anger disconnects us from nature, which could be understood not just as the rest of the world, but also from our own nature. In book 2, chapter 10, Marcus portrays the angry person as turning away from reason with a sort of pain or spasm.

Marcus also writes of anger and flattery as bringing “harm”. Some of the translations read in that this is harm to the person feeling anger, but the Greek is less definite than that. We could expect that the harm would be not just to those who get angry or give in to it, but also to those towards whom they direct their anger. Here one might respond that, from a Stoic perspective, strictly speaking whatever one does to another out of anger isn’t doing them any real harm, but to take that position — which easily fosters excuses for one’s own bad behavior — would be deeply mistaken. A genuine Stoic doesn’t expect other people to also believe and behave as Stoics. They can be harmed by our words, actions, attitudes that stem from anger. We must also keep the demands of the virtue of justice in mind as well.

Anger, “Manliness”, and Strength

The second part of the passage sandwiched between points nine and ten is a bit longer. Here’s the Hays translation:

When you start to lose your temper, remember: There’s nothing manly about rage. It’s courtesy and kindness that define a human being — and a man. That’s who possesses strength and nerves and guts, not the angry whiners. To react like that brings you closer to impassivity — and so to strength. Pain is the opposite of strength, and so is anger. Both are things we suffer from, and yield to.

Marcus uses the term prokheiron, a common Stoic term meaning that this advice is something we ought to have “ready at hand”, and the occasion is when we have instances — plural — of anger.

The adjective “manly” renders the Greek “andrikon”, which can certainly be translated that way, but which also echoes the important term andreia (used just a little bit later), the Stoic virtue we can translate as courage, bravery, or fortitude. The next line reflects this ambivalence explicitly, suggesting that the proper course of action is one that is both “more human” and “more manly”. And what sort of behavior deserves these qualifiers? Quite literally calmness or gentleness (to praon), the opposite of anger, and peacefulness.

I do have to admit that I like the choice “angry whiners”, which compresses together two different but connected terms that are part of the extensive vocabulary of anger in Greek. One of these is aganaktounti, signifying that the person is question is indeed angered, and the other is dusarestounti, conveying irritation, annoyance, and perhaps in this context petulance. So, “angry whiners”. I suspect if Marcus were around today and speaking in colloquial English, he might call these people out as whiny, wimpy bitches.

Real strength and sinew — and indeed courage (andreia) — doesn’t belong to the irascible or irritable, the complainers and shouters, according to Marcus, but only to those who can develop, deploy, and display gentleness and peace in tense situations. Susceptibility to anger represents a kind of brittleness, we might say, a weakness within that inevitably is shaken from without and reacts against the outside.

Notice too that Marcus speaks about impassivity, a condition that provides a key value and goal for the Stoics. This is something that we can make “more our own” (oikeioteron), so to speak, or increase within ourselves precisely by doing our best to curb our anger in favor of good temper or calmness.

Just as in the other passage just previous to this one, what Marcus is providing is a cognitively-based remedy. Anger tends to make us think along certain characteristic lines (I’ve been insulted by that person, and I shouldn’t take that, so I should retaliate), which tend to dominate our minds, crowding out or dampening other, more productive and positive lines of thinking. So with some preparation, effort, and choice, we can learn to supply those perspectives to ourselves when needed. For some of us — and Marcus must have been one such person — the disconnect between manliness and humanity on the one hand and losing one’s temper on the other is something that needs to be stressed.

I’ll be following this first article up soon with further posts giving similar treatments to the other ten points.

Gregory Sadler is the president of ReasonIO, a speaker, writer, and producer of popular YouTube videos on philosophy. He is co-host of the radio show Wisdom for Life, and producer of the Sadler’s Lectures podcast. You can request short personalized videos at his Cameo page. If you’d like to take online classes with him, check out the Study With Sadler Academy.

Thank you for the interesting article.