Lessons From A Fall: Experiencing And Dealing With Pain

reflections on the pains we feel spurred my a recent accident

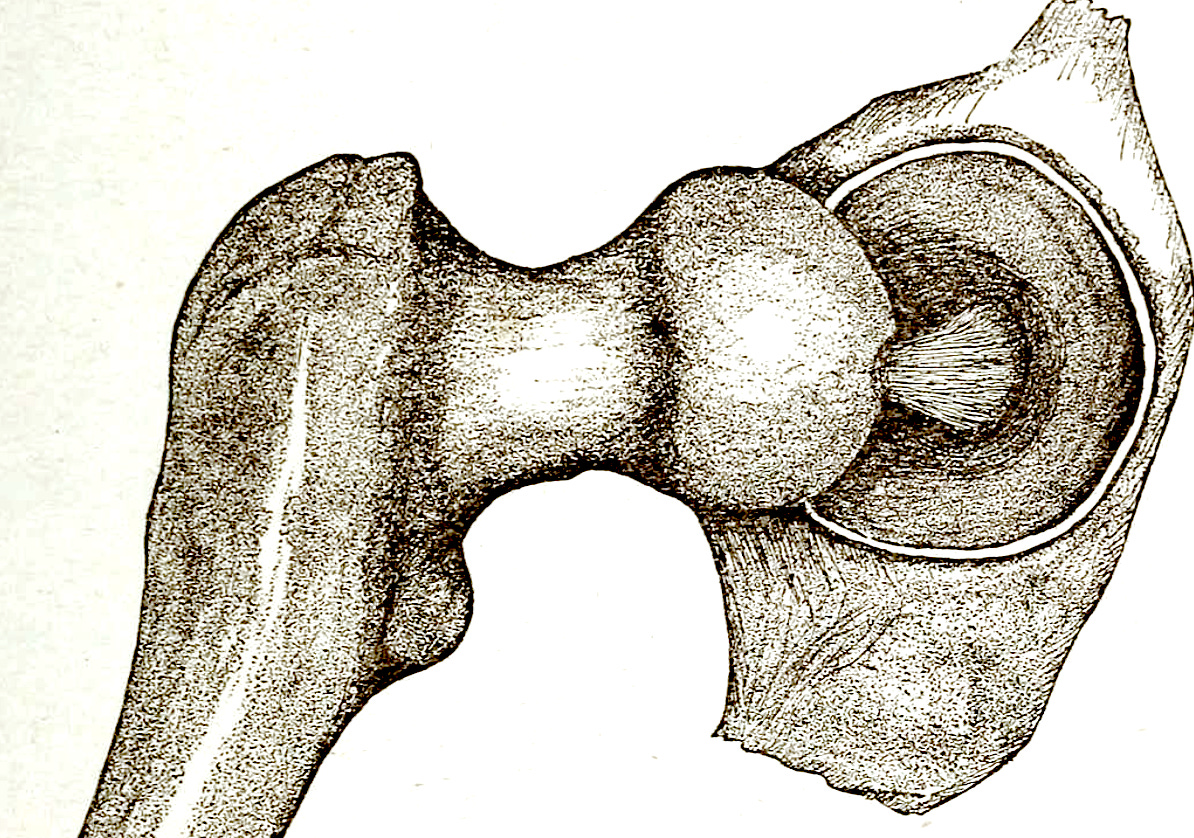

As many of you readers know, most likely from the earlier post in this ongoing series, about three weeks ago, I slipped at home, fell on my hip, and shattered the socket. Two days later at the hospital, they performed a complete hip replacement surgery. Three days later, I went home, and that’s where I have been since then, resting, recuperating, healing and doing PT, and slowly reincorporating work, first with my classes and students, then with clients, even fitting in a short online conference presentation.

One of the upsides of going through this sort of accident, operation, and recovery is that you not only get plenty of time to think about matters, but some of the experiences you have provide food for thought as well. Today, the one I’m going to write about is something all of us inevitably face sooner or later in life: Pain.

Right after the moment my foot slipped out from under me and I fell hard onto my hip, the pain hit me. I’ve had my share of colliding various body parts with harder stuff over the course of my not-always-prudent life, so the pain I was feeling, I hoped, was just from the impact, and that in a few minutes, I’d be able to sit up, get my bearings and deal with the injury. That was not the case. Just trying to move, I realized I couldn’t do much effectively with my right leg. I also went into shock, and started feeing so cold that my teeth were chattering.

Andi, my wife, didn’t have it easy through all of this. She tried to help me figure out how much damage I’d done, and assisted me to leverage myself up into one of our chairs. It became clear, every time I tried to put any weight on my right leg, that there was no way that even with her assistance, or with the crutches she brought me, that I was walking out of the apartment and down to the car. What told me that? The pain I felt. There was the pain from my hip that had become a constant. And then there was the pain that skyrocketed with any attempt to put any weight on the leg.

Long story short, we got out of the apartment and down to the car, and Andi drove me to the emergency room. The ER doc was skeptical at first. 55-year-olds don’t typically break their hips, he said, and then he started manipulating my leg. The pain I felt and my response made him decide to order an x-ray. When he came back with the radiology results, his attitude had completely changed. They looked bad, and he clarified that it was now time to transfer me by ambulance to the ER at the main hospital campus. Before that, they also started giving me some real painkillers, instead of the over the counter stuff they had.

The next several days, before and after the hip replacement surgery, would be marked by pain, immobility, and some other unpleasantness, which was alleviated physically by the generally good nursing staff, and still more psychologically by Andi’s presence, conversations, and care. They recorded a lot of measurements, multiple times per day. The took vitals quite frequently, stuck me for blood sugar readings before meals, and asked questions about pain levels over and over.

I think everyone is by now familial with the pain charts you see in American hospitals and clinics, where you select a number from 1-10 that is supposed to provide insight into the subjective experience of the pain a patient is feeling. There are all sorts of problems that arise as soon as you start thinking about the numbers we assign, but that’s not really where my focus is for this short reflection. Instead, I’m going to discuss three things I noticed and realized.

The first is that, in my case, it didn’t make sense to try to settle on just one overall number at any given point in time, precisely because I had varying levels of pain in different places. There was the hip joint itself, which had a good bit of pain until they did the surgery, and then that ended, because you don’t have any nerves in a titanium hip socket. There was the knee, where for decades I’ve feel pain rather frequently, but which was now since the fall almost always hurting. Something similar was the case for my IT (Iliotibial) band, but the pain there was pretty intense. I had some pain in my quadriceps as well before the surgery, and then much more there after, not least because the incision they made for the hip replacement went right in through the front of my thigh. So when they would ask: “What’s your pain level?” I’d say what those different levels were for each of those four places. And the nurses and assistants seemed all right with that.

The second thing was that if you gave them certain numbers, you’d cross a threshold where they would give you more painkillers. Here in the USA, in recent decades, we’ve gone from one extreme to another when it comes to painkillers, especially opioids. For a long time, they were doling them out at far higher levels than was prudent or warranted, the governing idea being that we ought to do whatever we can to alleviate pain. For years now, we’ve been at the other end, where medical professionals are leery of giving patients painkillers except at often-too-low doses, and sometimes even at all. I noticed after a while that if I said my pain levels topped out at a six, I’d get one dose, but if I said that magical word seven, they’d give me double that dose. I’ve got no interest in taking more than I need, so I didn’t report my pain being at a seven unless I really felt that was the case. But I can see how others might be tempted to report higher pain levels in order to get more drugs.

The third thing didn’t happen for a number of days. There was a whiteboard across the room that had slots for staff to write all sorts of things down, for example who the nurse that shift was, what I was allowed to do by myself or with assistance, and the like. One of the slots was for the goal pain level, and that was left empty nearly all of the time I was in there. It was only later on that one of the nurses, a particularly attentive one, asked me not just what my current pain levels were, but what my ideal pain level would be.

That threw me a bit, and I didn’t have an answer at first. The chart runs from one to ten, so one answer a person might feasibly give would be “I’d like to be at a one”. To me that seemed entirely unrealistic. She asked me again, and suggested: “maybe you would like to be at a two?” I thought about that for a minute, and then explained my situation. I deal with daily chronic pain, and have done so for years. Most days, I’m lucky to be hit a two. Some level of pain is nearly always there for me, just sort of in the background, and it doesn’t bother me very much. I only notice it when it stands out, that is, when it spikes to some higher level.

So given everything my body had recently gone through and was recovering from, aiming for a two seemed silly to me. That makes sense, she said. So what level did I want to aim for, realistically? I had to think about it for a bit, and I settled on a four. That seemed reasonable enough to me. I can be at a four and sleep all right at night, or work effectively during the day. I notice that level of pain, but it doesn’t really bother me too much. Would that be the case if I didn’t have that constant buzz of pain in my background? Probably not.

That raises an interesting and more general point that I discussed with a good friend of mine earlier today. Things like pain aren’t good. All things being equal, it would be better to have none or at least less of it. But when it’s a common experience for you in your life, the constant pain that you’ve felt and continue to feel might help you deal more readily with new, more intense pain. It gives you a sort of more realistic view on matters. It can work similarly with suffering from some measure of depression, or having experienced some degree of poverty, or I imagine many other negative challenges that a person might face. Dealing with some lower measure of them over time, long-term, can make running into more of the same at a higher level for a shorter time more bearable. And when it comes to relief from the higher level of the negative, you might be able to need less or lower relief than others in order to feel all right.

Gregory Sadler is the president of ReasonIO, a speaker, writer, and producer of popular YouTube videos on philosophy. He is co-host of the radio show Wisdom for Life, and producer of the Sadler’s Lectures podcast. You can request short personalized videos at his Cameo page. If you’d like to take online classes with him, check out the Study With Sadler Academy.

Wishing you a speedy recovery.

Hoping for a speedy and successful recovery for you.