Get Your Stories About The Dead Before They’re Gone For Good

ask and learn about those you love, but have lost — otherwise it’ll be too late

(an earlier version of this piece was previously published in my Medium publication)

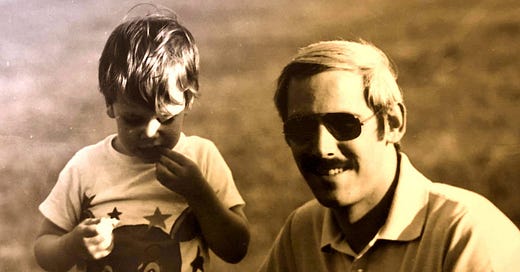

My dad died about 42 and a half years ago from today. It was 1982. He and my mom were both 36 years old, and that was all the time that he was going to get. I was 11 years old when he died, about to turn 12 later that month. And my little sister was just 9 years old. His death was a shock but not, at that point, a surprise. He had been languishing in the hospital — for the first few weeks at our so-so local one, and then for more than two months at the Mayo Clinic. None of the doctors were able to determine what was killing him, and they listed the cause of death as “fever of unknown origin”.

I’ve taken to commemorating the day he died in my own ways throughout my life. Some years back, when we were still living in our tiny “carriage house” apartment in Kingston, New York, I shot a fairly lengthy video reflecting upon my dad’s death, what it meant to us as a family, and my memories of him (you can watch it if you’d like). I posted it a long time back in my social media, along with some photos of my dad that my sister had sent me some time ago.

One of my Facebook followers picked up on one of the things I said in the video. I have been mulling it over since then, and I thought it might be worthwhile to write down some of my thoughts, expanding this hard-learned life-lesson.

“If you wanna know stories about people; you gotta get those stories before all the people who know those stories themselves disappear” This really has stuck with me.

That’s it: if learning the stories about the person you have lost matters to you, don’t take it for granted that you’ll always have the opportunity to ask about, and hear, those stories.

Losing Tony Sadler

Losing my dad proved a calamity for me and for our family. Of course, however bad it was for us, it was far worse for him. A brilliant, witty, hardworking, loving man had his life taken from him hour by hour, stuck in a hospital bed, in what should have been the prime of his life. He knew he was leaving behind his wife and children (and his own widowed dad, who was living with us) to an uncertain and grief-haunted future without him.

August 1982 passed in a blur. My Aunt Bibianne and Uncle Scott giving me the news as I sat in the back of their car. Riding back from the Lemrise family complex in Indiana, where I had stayed much of the summer, to our house in the township of Delafield, Wisconsin. Family and friends arriving. Playing with other kids in the yards. An Irish wake in our house, organized by my mom’s high-school friend, Marcy Butler.

The funeral mass, followed by the service at the funeral home in Wales. Saying thanks to people expressing their condolences. Hiding out places to read, and trying to figure out what I was supposed to feel and to say. Then everyone gone, just us — my mom, my sister, my grandpa, our dog Lady, and me — left in the house. A dreary attempt to celebrate my 12th birthday.

Then back to school for 7th grade, having to figure out what to say when everyone asked: “How was your summer?” I remember all of us having to say on the first day of class what we did over our summer vacations. All I could say was that I had watched my dad die, and that pretty much stopped that classroom exercise.

Time went on, and we lived with, and in, the absence of Tony Sadler. We were in rough shape financially. My mom went back to work, at first in an office supply store in Waukesha owned by one of our neighbors. The week after the funeral, another neighbor bought the 23-foot cabin cruiser my dad had had picked out, upgrading from our earlier 18-foot tri-hull — he was making good money as a tax attorney — off us, arguably taking advantage of my mom’s grief. Most of my dad’s life insurance went towards his medical bills. My mom later told me that if my grandfather hadn’t started paying us rent, we would have lost the house.

Being a solid earner, and managing the money well, was just one side of my dad. The lack, the missing, the loss was of a guy who, despite routinely working more hours than I do, made the time to take me fishing, to plan family camping trips, to coach my sister’s soccer team. He discovered me working on a play, urged me to develop it, contacted my drama teacher about it, and took off early from work to drive an hour to see the performance. He was outgoing, loved by so many members of my mom’s massive and close-knit Lemrise family. He was a brother to my uncles on that side, a son to my mom’s mom and dad, someone who fit in and who loved being with them. I could go on and on from my own stock of memories.

Not everything about my dad remained available, stored away in that memory bank, though. I had a single cassette tape containing a recording of my dad talking on it. After I couldn’t remember on my own what his voice sounded like — and it only took a few years for that to be the case — I would every once in a while pop that tape in and listen to it. You can guess what eventually and inevitably happened. With enough plays, the tape stretched, and then got tangled in the player heads, and broke. There were temporary fixes, but eventually there was no tape left. And with that, the last sounds of my dad’s voice were gone.

Losing Monique Sadler and Her Stories

Still, in my teenage years, I had a number of people from whom I could learn more about my dad — relatives, friends, even work-colleagues and neighbors who would tell me stories, either asked for or unprompted — and although that didn’t fill in the hole left in our lives by his loss, it did help out in some ways that I didn’t really understand then, but now can articulate and make sense out of.

One of the aspects of losing a parent early on in one’s life is that you can be stuck with them at the age they died. When I was an 11-year old kid, my dad had a relationship with me that matched that age. He was an adult, approaching middle age, a parent, a guy with a job, responsibilities, a track-record, a character, a history. Dying in some sense fixed him at that point.

Whatever illness it was that took him down robbed him of being any older than that, of moving into later decades and life-stages, and of continuing our relationship as I grew older. Many times I have wished that he were around for me to talk with, not just as son to father, but as a grown man to another grown man, as a new father to a grandfather, as one hard worker to another.

I didn’t get to know my dad as others do theirs (if they choose to), through living through years together, continuing the communication through change. But I did get something like that secondhand, through hearing the stories about him that others could tell me as I got old enough for them to be told to me. Of the two people who told me the most about my dad after my death, one of them — my grandfather, his father, Josef Sadler (born Josef Skufca) — died while I was in the Army over in Germany in 1990.

The other person was my mom, Monique, and I was fortunate that she was the open, talkative, intelligent person she was. Some widowed spouses might have dealt with their grief for their lost love either in silence or stereotyped tales. Instead from time to time, she would tell us stories that revealed to us sides or aspects, events or offhand sayings, we didn’t already know about our dad. And the range of topics expanded as my sister and I grew older, as we moved from our teens into our twenties, and in my case, as I left for the Army, then went to college, then worked, and went off to grad school.

Late in January of 2000, I got a call from the US Consul in Costa Rica, informing me that my mom had drowned in a rafting accident, telling me a death certificate would be sent shortly, and asking me how I wanted her remains delivered. My mom was 53, I was 29, and my sister (now pregnant with a first grandchild my mom would never see) was 27.

By this point, I had gone through the deaths of my dad and his parents, my best friend, a sort-of girlfriend, and quite a few of my mom’s relatives in my grandparents’ generation. With some help from my sister, I handled the funeral arrangements, my mom’s boyfriend’s attempts to get sympathy and claim equity in her house, and the complexities of her finances and the estate.

Losing my mom was a double loss, I came to realize over time. Once again, one of my parents was fixed in time, never to get any older, never to share in the changes and developments in our life, never to change and grow anymore themself. My sister and I were now the oldest and only surviving members of our little portion of the Aime-Bibianne branch of the much larger Lemrise family-clan. We could turn to the rest of them for stories about my mom, and to a lesser extent my dad. But along with my mom dying, so were all of her perspectives, all of her memories, all of her jokes, all of her insights not only about herself, but also about my dad and about the life they had built together.

Had I known that she would die, not as young as my dad, but still long before her time, I would definitely have used some of the time we did have together to get to know her much better, to more fully build out the image of her I still carry in my heart. And I would have drawn much more upon her as a resource to do the same with the stories she could have told about my dad, her husband, the love of her life.

I would have made greater efforts, made the 8-hour trips back home to Milwaukee from Carbondale much more often, spent more time in conversation with her, or even just hanging out together, instead of doing the myriad other things you do when you don’t have any suspicion that you might not get more opportunities to spend time with a person.

Bittersweet Realizations

Even though I didn’t get anywhere near the amount of time others typically have with their parents, I still consider myself incredibly lucky to have been adopted by Tony and Monique Sadler. My sister and I, adopted from different biological parents, were told as far back as we remember that we were adopted, but we were also loved, cared for, fostered, and not just by our parents, but within the matrices of their families as well. There were struggles, conflicts, arguments, misunderstandings — every family has those (and those that “don’t”, really do — you just don’t see them) — but apart from my dad dying, we had some overall good childhoods.

I’m fortunate as well not just to have had good parents for the time that they were with us, but to have built up a treasure-house of memories about them that — while they may be faded and fragmentary, and the sound is lacking to them — I can call up and reflect upon when I choose to. I can also be thankful that there are still some people still around in my mother’s Lemrise family who I can still reach out to and talk with about both of my parents.

And yet, everyone else who is left has much less to impart to me about my dad than my mom, gone now for twenty-five years, would have been able to tell me. And as I myself approach and will likely pass the age she reached, there are fewer of those who can tell me much about her. Her brother Aime passed away several years back, and it’s just her other brother Jean-Marie and her little sister Bibianne who are left.

There’s other of cousins to be sure, but I don’t see them often, and quite a few of them have also passed on. Nearly the entire generation of my grandparents are gone as well. The opportunities for asking about and hearing new stories, or even the same old ones over again, are slipping away.

Of course, all of this assumes that one wants to learn those stories about those one has lost, and that isn’t the case for everyone. There might be some people one would rather forget. One might also be at a stage in one’s life when these matters seem less important than other things that occupy one’s attention and desires.

Then again, the younger you that feels — and prioritizes — that way can’t really predict what the older you will want, need, and wish you had done later on down the line. I’m living out precisely that reality now. I wish I had asked more questions, listened better to what was said, and requested more stories about my dad, about my mom, from my mom about my dad, or from my grandparents about my mom.

So the lesson here is precisely what the title tells you: Get those stories — about the people you love but have lost — before they’re gone for good. You can’t take it for granted that the storytellers themselves will always be around.

Thanks for re-sharing this, Greg. I will be including this in the February Bazaar at Stranger Worlds.

With unlimited love,

Chris.

What a blessing, being loved as you were, are. Myself born into a sea of extended family and with my siblings, heard story upon story of the grandfathers who died too young, my grandmothers lives, and unexpectedly, got to live lives filled with each of our own long-lived parents. I tell my grandchildren stories I heard. Bright faced young ones, hearing about a great-great grandmother sent ‘into service’

at age 7, to a household on the outskirts of Istanbul….

But yes, how many times do we sit and ask each other ‘did dad ever tell you about…? Or how did mom get from point a to point b back then? Who did she stay with? Wow look at that photo - where were they?…”. Unanswered, all of them, now..