Class Reflections: Medea And Her Anger

a classic tragedy opening up issues about this emotion

We are in the third week of my online Anger, Justice, and Action class at Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, which meets for class sessions on Monday afternoons. This week, the readings I assigned and discussed with my students are Euripides play Medea and a few passages from Epictetus’ Discourses about Medea.

That play (and the central character it is named after) is a classic reference point in ancient discussions about the emotion of anger, and examined by quite a few late modern writers on anger as well. Why is that?

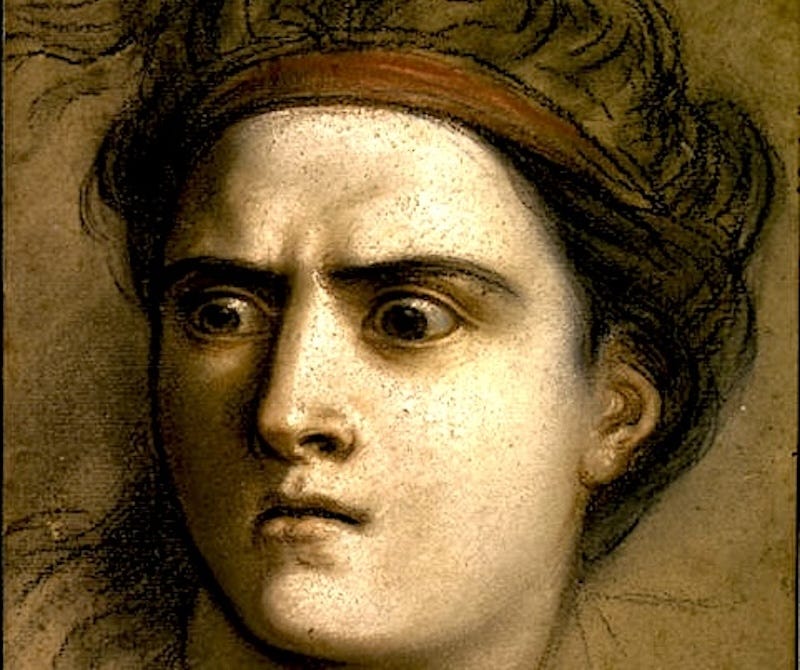

It might be in part because in it we have a very strong female character, the sorceress and princess Medea, who in order to impose her revenge upon her husband Jason, arguably one of the more pathetic among the Greek heroes of legend and myth, kills her own children.

I think another aspect of the play, which thematizes anger not only on her part but also on that of other characters, for example Creon the ruler of Corinth, is that in Medea we have a clear example of someone depicted as knowing that she should not give in to her anger, that what it bids her to do is wrong, but follows its dictates anyways. This is a case of what in Greek is called akrasia, often translated as “weakness of will”, “incontinence,” or as I prefer “lack” or “loss of self-control”. In this case, it is what Aristotle would call a type of “qualified” akrasia, namely akrasia in relation to anger.

There are a number of Greek tragedies where anger and other connected affects play a central role. Many of the characters in Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy are motivated by anger, and the Furies in the third play of that cycle, the Eumenides, are a sort of personification of wrath. The emotion also figures into the decisions of the characters of Sophocles Theban trilogy, and is absolutely central to another of his plays, the Ajax. Anger figures into the plots and characters of a number of Euripides’ plays as well, and arguably more in his Medea than in any other ancient Greek tragedy.

Much of the course has the students engaging with philosophers’ and theologians’ treatments of anger, but I like to begin our semester with more literary depictions of the emotion, where there certainly is some theorizing going on, but where the emotion, its causes, and its effects get dramatized in ways that will draw the students in. Next week, we shift gears and look at what Plato has to teach us about anger, and then after that, Aristotle. So the Medea provides a useful launching point for some serious thinking together about how anger works, what it is, and what it does to us.

What Is Medea Angry About?

If you’re familiar with the story of Jason, his ship the Argos, and the golden fleece, you already know well who Medea is. She is a princess of Colchis, a country on the Black Sea. She may have been a princess of Hecate, who she invokes at one point in the play, but she is also a powerful sorceress, and a very dynamic and passion-driven person.

Jason is a kind of second-rate hero, the son of Aeson who had been deposed as king of Iolcos by his half-brother Pelias. Pelias assigns Jason the task of stealing the golden fleece from Colchis, as a price for the kingship, and Jason assembles a crew of heroes, the Argonauts, with whom he sails on the Argos to Colchis, hitting some places and having some adventures on the way and back. A top-tier hero Hercules helps him for a while on the way there, and Medea helps him on the way back.

In fact, if it wasn’t for Medea choosing to favor Jason over her own homeland and family, there’s no way Jason could have survived in Colchis, let alone gotten the golden fleece. And when he is fleeing back home, pursued by Medea’s father the king, Medea murders and dismembers (in one version) her own brother to secure their escape. She even helps Jason deal out revenge on his uncle Pelias, for which both of them are banished. So all told, Medea has done a lot for Jason.

How does he repay her? They have two children together, and eventually settle in Corinth, and there Jason eventually decides that it is time to “trade up” (to use the parlance of contemporary immature men who leave their faithful spouses for younger women). He gets engaged to the daughter of the king of Corinth, which will certainly make him better off, no longer an exile. But it means that Medea and their two children will be cut out not just from their little family, but exiled from Corinth.

She certainly has understandable and legitimate grounds for anger. She and her children have been deeply wronged by the one person who least has grounds for doing so. She gave up her family and her homeland for Jason, and was instrumental in whatever successes he had from the point that they met onward. He shows himself to be a betrayer and an ingrate. Interestingly, it seems that few of the Corinthians see anything wrong with what Jason is doing, and instead they tell Medea not to do what she is doing, or what they think perhaps she might be compelled by her grief and anger to do.

Medea expresses a number of emotions, which to me seems a great depiction of the mixed-up emotions we often feel when faced with crises of betrayal like the one imposed on her. She talks of pain, misery, grief, suffering, and expresses the wish she could just die.

Her anger and hurt spills over against others as well, for instance:

O my children,

cursed children of a hateful mother—

may you die with your father and his house,

may it all perish, crash down in ruins!

Notice that her desire here is that Jason suffer and perish, and her children are you might say “collateral damage”. Just a bit later she says:

O how I want to see him and his bride

beaten down, destroyed—their whole house as well—

for these wrongs they dare inflict on me,

when I’ve done nothing to provoke them!

That really is the central point. She has done nothing wrong to them, her husband, his new bride, her father and their house. In fact, if it were not for her giving up her own family, and aiding Jason at so many points, he wouldn’t even be there to marry the young princess of Corinth. If anyone has a right claim to be angry and exact some sort of retribution, it would seem to be Medea.

Creon, the king of Corinth, will turn her very own words said in anger into an excuse to banish her and her children from the city, grudgingly granting her only one day:

You there, Medea, scowling in anger

against your husband. I’m ordering you

out of Corinth. You must go into exile,

and take those two children of yours with you.

….

I am afraid of you.

I won’t conceal the truth. There’s a good chance

you might well instigate some fatal harm

against my daughter. Many things lead me

to this conclusion: you’re a clever woman,

very experienced in evil ways;

you’re grieving the loss of your husband’s bed;

and from reports I hear you’re making threats

to take revenge on Jason, on his bride,

and on her father

Later on, when she and Jason are on stage confronting each other, he rather implausibly tries to claim that he is actually looking out for her and their sons as they are about to be exiled. In his view, Medea by her own fierce temper brought about the situation they now face. She should have gone along with matters and not angered Creon. When you understand the situation and read Jason’s rather self-serving take on it, it’s hard not to despise him

Her response, which includes a long discussion of all that she has done for him over the years, attacks him at his core.

As a man you’re the worst there is—that’s all

I’ll say about you, no trace of manhood.

You come to me now, you come at this point,

when you’ve turned into the worst enemy

of the gods and me and the whole human race?

It isn’t courage or firm resolution

to hurt your family and then confront them,

face to face, but a total lack of shame,

the greatest of all human sicknesses.

But you did well to come, for I will speak.

I’ll unload my heart, describe your evil.

You listen. I hope you’re hurt by what I say.

Where Does Medea Go Wrong?

The play functions as an interesting litmus test, I’ve observed, for people’s attitudes about anger, and more specifically about who is allowed to be angry. Medea is a double-sided character.

On the one hand, she is a powerful, passionate, devoted, and intelligent woman. It will turn out that she is indeed quite capable of formulating and carrying out a multi-part plan of revenge that results in the deaths of the wife and father-in-law to be, the deaths of her own children, and the devastation of her unfaithful ingrate husband Jason. And escaping Corinth on a chariot of dragons, she gets away with her revenge as well.

On the other hand, Medea is a woman, which in ancient society places her at a great disadvantage, a point she makes in the play. She and her children are foreigners in the city of Corinth. And with Jason throwing her over for a new, well-connected bride, she and their sons are now effectively exiles and refugees. All of this places her in the class of the vulnerable, those oppressed by clear injustice.

To me it is always telling who people think have a right to be angry, to express that anger, to act upon it, and those they think do not. There are many people in our contemporary society who seemingly have no problem with the rich, the powerful, the privileged lapsing into and indulging their anger, but who condemn and fear the anger of those who are disadvantaged, vulnerable, already victims of injustice. That strikes me as a serious defect of character on their parts. Being cool with men being angry, but wanting women not to be angry is a common instance of this.

The only two people in the play who seem to think that Medea should not be angry or express her anger are Jason and Creon. The Nurse, the Chorus, and their Leader take more ambiguous in their stances. They fear that she will hurt her children, and rightly so, but they understand her pain and her anger.

Do the gods condemn Medea’s anger, or even her terrible pedicidal revenge? It doesn’t seem so. The chariot she makes her exit on is a gift of Helios. She invokes Artemis, Themis, and Hecate. Even the Furies, the punishers of kinslaying, who Jason tries to evoke, aren’t going to go after her. She retorts:

What god or spirit listens to you,

a man who doesn’t keep his promises,

a man who deceives and lies to strangers?

My students could certainly sympathize with Medea, and for the most part in our discussion, they thought that, while extreme, her retaliation against Jason’s new bride and her father were understandable. It is a violent society, and she has been wronged. Some of them did think that her revenge should have been more direct, targeting only Jason, for instance, by killing him.

Where everyone agrees that she goes wrong, both in the play and among my students, is in killing her own children. Notice that she does this as a deliberate act, not as a simple “crime of passion” where she sees red, loses complete control, and then finds the corpses of her sons afterwards. She provides two reasoned justifications for why she does it. One is to get revenge upon Jason. The other is to keep them from being exploited, abused, or killed as refugees in exile. Neither of these are acceptable justifications for taking her children’s lives.

It is worth pointing out, however, that Medea tells Jason that she intends to carry out burial rituals for their sons:

My own hands will bury them.

I’ll take them to Hera’s sacred lands

in Acraia, so no enemy of mine

will commit sacrilege against them

by tearing up their graves. And in this place,

this land of Sisyphus, I’ll initiate

a solemn celebration, with mystic rites,

future atonement for this profane murder

She hasn’t simply discarded them. In fact, this is as much of a loving gesture as is possible for her at that point.

Why Does Medea Do It?

Medea knows right from wrong. She is capable of pretty extensive reasoning. She provides a solid portrayal of a person who can both feel and think deeply, and this aspect of her character points us — and many theorists of emotion — towards one key insight about anger.

Some people who feel anger seem to effectively get their minds shut off. They fall into a rage, like Sophocles’ Ajax in that earlier-mentioned play. But that is definitely not how everyone feels and is affected by anger. In Medea’s case, she is certainly capable of deliberating about the best means to attain her revenge.

I’ll turn three of my enemies

to corpses—father, daughter, and my husband.

Now, I can slaughter them in many ways.

I’m not sure which one to try out first.

Perhaps I should set the bridal suite on fire

or sneak into the house in silence,

right up to their marriage bed, and plunge

some sharpened steel right through their guts.

There’s just one problem. If I get caught

entering their house meaning to destroy it,

I’ll be killed, and my enemies will laugh.

No. The best method is the most direct,

the one at which I have a special skill—

I’ll murder them with poison.

She even goes on to think over what the consequences of exile will be, whether she might find an ally somewhere in Corinth, and the need for a plan B if the poisoning goes awry. We can say that her capacity for practical reasoning not only is not shut off by her anger, but it is being harnessed by it.

As she is readying herself to kill her children, she says two lines that have captured the attention of many subsequent thinkers:

I know well what evils I am about to undergo, but my wrath overbears my intention,

wrath that brings mortal men their gravest hurt.

“Wrath” there translates a very important Greek term for anger, thumos. Plato and the entire Platonic tradition will make that one part of the human soul, the part that is focused on honor and winning, the part that gets angry and where courage or cowardice can be situated. Aristotle makes it one primary type of affectivity or desire, and notes that our higher rational faculties can be overcome by it.

This conflict within the human person who is in the grips of anger, in Medea’s case, entirely legitimate anger, who feels strongly its drive and desire for revenge and retribution, and at the same time also is at least partly in control of their faculties, that is one of the lessons of the play, namely that this situation is a possibility for us human beings. And it provides an opportunity to reflect upon anger, a part of ourselves, and its capacity to take us over, seducing our rational capacities into its service.

That is Angry! To kill your own Children. That's rageful anger.