Boethius on Mistaken Views on Human Happiness

learning what’s really good for us in his Consolation of Philosophy

(this was previously published in Practical Rationality)

One essay I often assign my Ethics students at the beginning of the semester is Alasdair MacIntyre’s Plain Persons and Moral Philosophy: Rules, Virtues and Goods (included in the Macintyre Reader). One reason I use that short piece is that it introduces an important theme, the idea that we are all, whether we realize it or not, involved in the processes of asking and answering certain fundamental questions:

. . . on an Aristotelian view, the questions posed by the moral philosopher and the questions posed by the plain person are to a certain degree inseparable. And it is with questions that each begins, for each is engaged in enquiry, the plain person often unsystematically asking”What is my good?” and “What actions will achieve it?” and the moral philosopher systematically enquiring “What is the good for human beings?” and “what kind of actions will achieve the good?” Any persistent attempt to answer either of these sets of questions soon leads to asking the other.

In MacIntyre’s view — and I think he’s right — we are all of us committed to one or another — some more some less consistently — to one moral theory or another, whether explicitly, consciously, deliberately so, or whether only implicitly, accepting it perhaps as the default, following a trajectory of desire we have failed, avoided, or even not had the opportunity to think out.

When we see these sorts of moral matters from a different perspective, we imaginatively place ourselves in the perspective of another, rival moral theory. When we leave one perspective behind and adopt another — whether by a gradual process or a sudden conversions — we shift our allegiance from one moral theory to another.

Moral Theory and Ordering Goods

In doing so — in having any moral theory to work with — we accept, even presuppose some ordering of the many, multiple, heterogenous and yet comparable goods which we experience or even just imagine. That is indeed a determinative set of features of each moral theory

what it takes to be good things

what it takes to be bad things

how it arranges, orders, compares them to each other

what kind of opportunities it leaves open or closes off

what sort of sacrifices it demands or denigrates

what rules and principles for moral reasoning it recognizes

and what sort of persons, what structures of motivations and desires, what concrete configurations of practical reason it holds out as models of good or bad.

MacIntyre, unapologetically (but not without reason) committed to a Thomist-Aristotelian moral tradition of Virtue Ethics fortified with Natural Law theory (after his transition from After Virtue through Whose Justice Which Rationality to Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry and beyond), says something very interesting in this short, rich, worthwhile essay:

A plain person who begins to understand his or her life as an uneven progress towards his or her good is thus to some significant extent transformed into a moral philosopher, asking and answering the same questions posed by Aristotle in the Nichomachean Ethics and Aquinas in his commentary on the Ethics and elsewhere.

What are those questions? Among them is: what is the highest good? What should the other goods constellate around and be understood in terms of?

The recurrent and rival claims of pleasure, of the pursuit of wealth, of power, and honor and prestige to be the ordering principle of human lives will each have to be responded to in turn; and in so responding, and individual will defining his or her attitude to those considerations which Aristotle rehearses in book 1 of the Nichomachean Ethics and which Aquinas reconsiders in the opening questions of the Ia-IIae of the Summa Theologiae, in the course of their extended dialectical arguments on the nature of the supreme good.

Aristotle, Aquinas, and MacIntyre

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Thomas’ so-called Treatise On Happiness both frame this set of questions and answers — careful and comprehensive consideration of candidates for the true, the final, the supreme good — in terms of happiness. What is happiness? they ask, and then examine all of the commonly held, plausible views upon that subject, those corresponding, as it turns out to most other moral theories one might raise up against their own as rivals.

Each candidate possesses some attractiveness, some reason why a person in grasping and seeking happiness under that object might think or feel him or herself to be on the right track. But, when considered carefully, each of those possible sources or embodiments of happiness turn out to be deficient, lacking something, unable to entirely satisfy, to serve as the final end.

I very much like both Aristotle’s and Thomas’ dialectical excursions into the marketplace, or rather bazaar, of ideas — and I actually teach both of those texts in my own Ethics classes, a course specifically designed to meet the needs of plain persons, rather than the indulgences of a professional philosopher. If you like, you can watch and listen to some of those class sessions here and here)

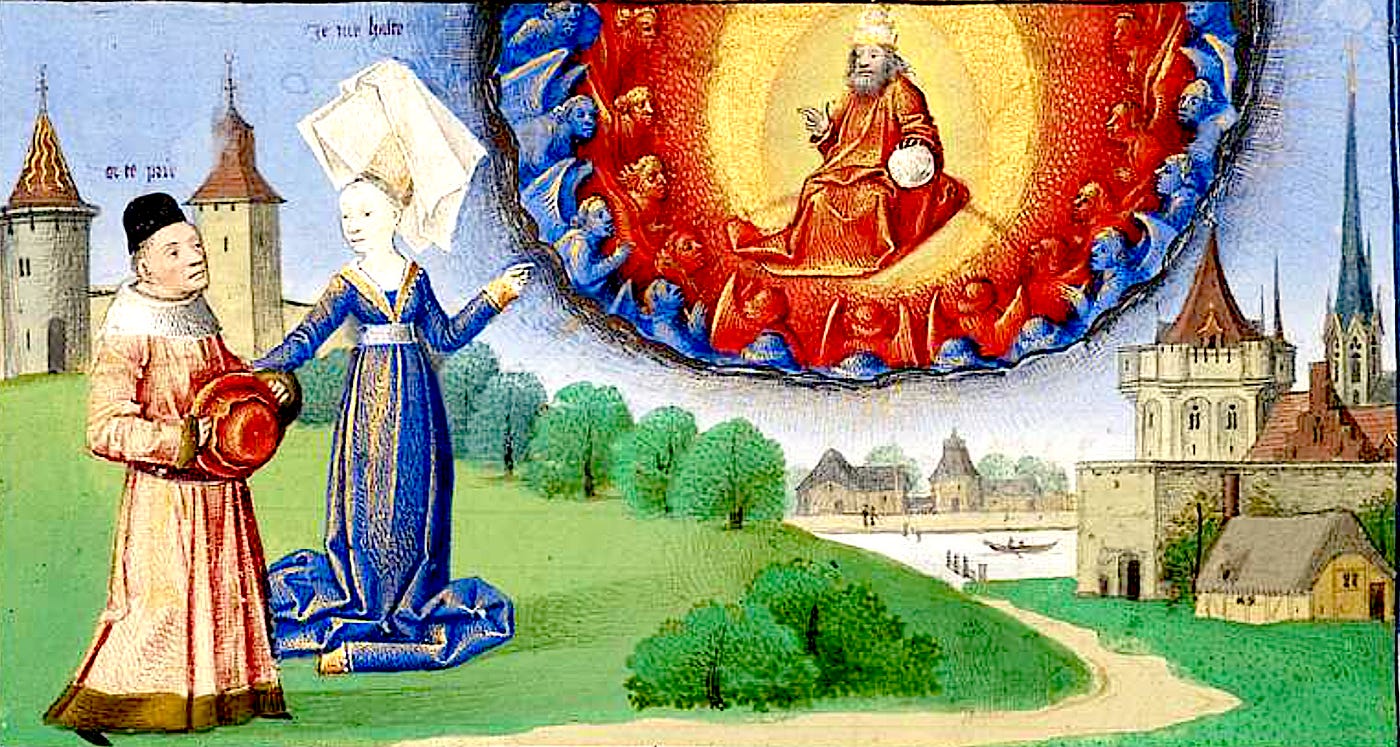

A considerable portion of Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy develops a similar line of practical reasoning, critically examining (or more properly speaking, remembering and revealing) the relative merits of the goods we often presume or decide to be happiness. The work is actually a dialogue in which Lady Philosophy herself comes to console the downcast Boethius, a victim of clear injustice, in his prison cell.

What does actually provide him consolation in those circumstances is being brought back to the right beliefs. Philosophia, as wisdom, or at least its pursuit, personified, engages in discourse, exhortation, dialogue with the glum philosopher and courtier, and among the topics over which they range is precisely: what is happiness? Who has got it right, and who has got it wrong? And most importantly — what makes this philosophical — why are the wrong views wrong? What’s wrong about them?

Philosophy, and Boethius following along with her, is engaged in precisely the sort of enquiry MacIntyre claims to be that of the moral philosopher. And yet, like everyone else, including professional academics, he is also a plain person, asking not only what is the good?, but what is my good? in determinate, and in this case even desperate circumstances, deciding what his narrative still being lived out will be.

Boethius’ own inquiry into happiness bridges the gap between a philosophical, universal moral inquiry into happiness and the personal, particular, even pressing situation in which he finds himself. I think just for that reason, that is, the fact that Boethius’ Consolation in some way exemplifies the interplay between universal and particular, joined by narrative and moral theory, it deserves a place in what one might call (a bit tongue in cheek) the MacIntyrian canon. Rereading the work, I noticed something else I found particularly interesting, something that takes its treatments of goods and happiness beyond those of Aristotle on Nichomachean Ethics book 1 and Thomas in the Summa.

Boethius on Good and Happiness

The rival goods not only fall short of happiness’ demands and requirements, revealing pocks and imperfections when examined by the critical eye. They not only fail to respond to the full exigencies worked into our natures as rational beings, which express themselves as desires and inclinations, even inchoate and inarticulate urgencies and sentiments, just as much as deliberately reasoned-out ends, plans, and resolutions.

In a series of dialectical progressions that would be reminiscent of Hegel if his own thought was not more than a millennium off in the future, the Consolation shows these goods simply to be shifting sand when understood in their ordinary senses. Whatever solidity they possess lies not in themselves, but where they meet in a good transcending and realizing them.

That’s enough preliminary, I think. Now on to some of the key passages, in which what I’ve described actually takes place.

. . . happiness is a state made perfect by the presence of everything that is good, a state, which, as we said, mortal men are striving to reach though by different paths. For the desire for the true good is planted by nature in the minds of men, only error leads them astray towards false good.

Some men believe that perfect good consists in having no wants, and so they toil in order to end up rolling in wealth. Some thing that the true good is that which is worthy of respect, and so struggle for position in order to be held in respect by their fellow citizens. Some decide that it lies in the highest power, and either want to be rulers themselves, or try to attach themselves to those in power. Others think the best thing is fame and busy themselves to make a name in the arts of war or peace. But post people measure the possession of the good by the amount of enjoyment and delight it brings, convinced that being abandoned to pleasure is the highest form of happiness.

Others again confuse ends and means with regard to these things, such as people who desire riches for the sake of power and pleasure, or those who want power for the sake of money or fame. So it is in these and other such objectives that the aim of human activity and desire is to be found. . . .

Will these necessarily bring happiness, though? Earlier, Philosophy reminded Boethius:

It is the nature of human affairs to be fraught with anxiety; they never prosper perfectly and they never remain constant. In one man’s case you will find riches offset by unwelcome publicity on account of the crippling poverty of his family fortunes. Some men are blessed with both wealth and noble birth, but are unhappy because they have no wife. Some are happily married but without children, and husband their money for an heir of alien blood. some again have been blessed with children only to weep over their misdeeds. . .

No one is so happy that he would not to change his lot if he gives in to impatience. Such is the bitter-sweetness of human happiness. To him that enjoys it, it may seem full of delight, but he cannot prevent it slipping away when it will.

None of the limited goods over which fortune has greater control than do we can make good on the promises they make. A few examples:

Wealth which was thought to make a man self-sufficient in fact makes him dependent on outside help. In which case, what is the way in which riches remove want? . . Far from being able to remove want, riches create a want of their own.

It is said, when a man comes to high office, that makes him worthy of honor and respect. Surely such offices don’t have the power of planting virtue in the mind of those who hold them, do they? Or removing vices? . . . More often than removing wickedness, high office brings it to light.

What sort of power is it, then, that strikes fear into those who possess it, confers no safety on you if you want it, and which cannot be avoided when you want to renounce it?

There is no support either in friends you acquire because of your good fortune rather than your personal qualities. The friend that success brings you becomes your foe in time of misfortune. And there is no evil able to do you injury more than friend turned foe.

What Goods Reveal Themselves As

At last we come to the first moment of dialectical transformation, where these seemingly so solid goods turn out to be empty, hollow, not only in comparison to something greater, but on their own ground, on their own account, on the basis of what they promised to the desiring human being.

There is no doubt, then, that these roads to happiness are side-tracks and cannot bring us to the destination they promise. . . .If you try to hoard money, you will have to take it by force. If you want to be resplendent in the dignities of high office, you will have to grovel before the man who bestows it; in your desire to outdo others in high honor you will have to cheapen and humiliate yourself by begging. If you want power, you will have to expose yourself to the plots of your subjects and run dangerous risks. If fame is what you seek, you will find yourself on a hard road, drawn this way and that until you are worn with care. Decide to lead a life of pleasure, and there will no one one who will not reject you as the slave of that most worthless and brittle master, the human body. . . . The sleek looks of beauty are fleeting and transitory, more ephemeral than the blossom in spring.

The sum of all this is that because they can neither produce the good they promise nor come to perfection by the combination of all good, these things are not the way to happiness and cannot by themselves make people happy.

The second important dialectical moment — one apparently negative but later leading beyond it to a positive development — lies in a realization of the seeming incompatibility of these limited goods.

If a man pursues wealth by trying to avoid poverty, he is not working to get power; he prefers being unknown and unrecognized, and even denies himself many pleasures to avoid losing the money he has got. . . And if a man pursues only power, he expends wealth, despises pleasures and honor without power, and holds glory of no account. but you can see how much this man also lacks; at any one time he lacks the necessaries of life and is consumed by worry, from which he cannot free himself, so he ceases to be what he most of all wants to be, that is, powerful. A similar argument can be applied to honor, glory, and pleasures, for, since any one of them is the same as the others, a man who pursues them to the exclusion of the others cannot even acquire the one he wants.

There is a riddle here to unravel — the good, the object and satisfaction of desire — seems to be necessarily scattered over all sorts of goods. The pursuit of any of them somehow excludes the other goods, and then places in one’s hands something other than the true object of desire.

Common Views on Happiness

Wealth, money, possessions, reputation, glory, power, offices — none of these external goods turn out to satisfy entirely — or even to make good on the promises they make, to provide the good specific to them:

No one doubts that a man in whom he has seen evidence of bravery is brave. .. In the same way music makes a man a musician, medicine makes him a doctor, and rhetoric makes him an orator; for it is the nature of anything to perform the office proper to it. It does not become mixed up in the operations of contrary things and actually repels opposites.

But riches are unable to quench insatiable greed; power does not make a man master of himself if he is imprisoned by the indissoluble chains of wicked lusts; and when high office is bestowed on unworthy men, so far from making them worthy, it only betrays them and reveals their unworthiness.

What other goods are there that offer the possibility of happiness? Just as much in our own time — in fact, in so many more ways — some see happiness residing with the goods of the body: one’s own physical attractiveness, strength, or a state of health, for instance, or beauty exhibited by physical things outside of oneself, which one can enjoy. Pleasure of all varieties is also a contender, is it not? But, that is not complete enough to be happiness — and often enough, the direct quest for pleasure ends up ruling out or cutting the seeker off from other desired goods.

Thus far, Boethius has traced a path similar to those of Aristotle and Aquinas, examining goods, desires for them, and the kind of life centered by them. Aristotle will propose two happy lives, one of engagement, active practice of the moral (and certain intellectual) virtues, and one of contemplation, pursuing and enjoying knowledge or wisdom.

Thomas Aquinas will go further and place full happiness in God alone. The goods or activities of the soul Aristotle identified with happiness are insufficient once placed within the theological horizon Thomas glimpses, though he does grant that happiness is experienced through the soul. Where does Boethius fit in? Somewhere between these two luminaries, as we’ll soon see.

The Unity of the Good

Philosophy identifies the fundamental mistake made by all those who consider external or bodily goods to be or to lead to happiness, and it’s not a mistake which takes the form of being entirely wrong, of having fully missed the mark, of giving an answer that is completely incorrect.

That which is one and undivided is mistakenly subdivided and removed by men from the state of truth and perfection to a state of falseness and imperfection.

Self-sufficiency, power, being revered or respected, even fame or glory — rightly considered, understood in terms of a being fully possessing them — coincide in one good, rather than compete as rival goods. The dialogue continues:

If there were, then a being self-sufficient, able to accomplish everything from its own resources, glorious and worthy of reverence, surely it would also be supremely happy?

How any sorrow could approach such a being is inconceivable; it must be admitted that provided the other qualities are permanent, it will be full of happiness.

And for the same reason this conclusion, too, is inescapable; sufficiency, power, glory, reverence and happiness differ in name, but not in substance.

That is — for modern readers — a rather startling conclusion. Admittedly, Boethius does not argue for this substantial identity of goods quite as well as one might like (as does, say, Anselm in his Monologion). But, set that aside for the moment, so that we can see where he takes this line of practical reasoning.

Human perversity, then, makes divisions of that which by nature is one and simple, and in attempting to obtain part of something which has no parts, succeeds in getting neither the part — which is nothing — nor the whole, which they are not interested in.

For Boethius, who is characteristically Platonist in this stance, the goods we encounter, experience, enjoy, are all merely imperfect participations in The Good. So, even when we abstract away from the individual particulars — this wealth and that wealth, this pleasure and that pleasure, and so on — to form more universal conceptions of wealth as such or pleasure as such, yearning then for the self-sufficiency wealth promises or the full and pure enjoyment with which pleasure draws our desires, these conceptions remain but partial, cloudy, and thus deceptive images of the genuine, undivided good transcending the realm and values of individual or imagined goods.

The Mistake of Separating Goods from The Good

Seeking any one of the goods of life in a way subordinating the others to it, negating, passing up, ignoring those other goods, becomes a losing proposition, a strategy guaranteed — on a metaphysical as well as moral level — to fail. After running through the dialectic of wealth, Philosophy notes:

A similar argument can be applied to honor, glory, and pleasure, for, since any one of them is the same as the others, a man who pursues one of them to the exclusion of the others cannot even acquire the one he wants.

But suppose someone should want to obtain them all at once and at the same time.

Then he would be seeking the sum of happiness. But do you think he would find it among these things which we have shown to be unable to confer what they promise?

She urges a reversal of perspective to Boethius, who complies, saying:

. . .true and perfect happiness is that which makes a man self-sufficient, strong, worthy of respect, glorious and joyful. . . . I can see that happiness to be true happiness which, since they are all the same thing, can truly bestow any one of them.

So, this is the condition to be sought after by human beings who really want to strive after the happiness, whose desire is indelibly implanted within the depths of our souls — but whose shape, form, content we can make so mistakes about. There is, however, another step which has to be taken:

Do you think there is anything among these mortal and degenerate things which could confer such a state.

No I don’t. . .

Clearly, therefore, these things offer man only shadows of the true good, or imperfect blessings, and cannot confer true and perfect good.

If you think about this for a moment, and you’re willing to indulge some flippancy on my part in the midst of such profundity on Boethius’s part, that’s a real kick in the pants at that point in the dialogue! Only such a state as has been sketched by Philosophy would be genuine happiness for a human being. But nothing within the realm of experience can provide or produce such a condition. It will turn out that God is and enjoys such happiness. But, given our difference from God, how does that help us?

Theosis, or Becoming-God

For Boethius, contemplation of God is an avenue into happiness. He calls knowing the good itself — seeing God — “infinitely valuable.” But, is that what happiness is, just contemplating something outside of, higher than oneself? Losing oneself, perhaps, leaving oneself behind, in that contemplation? As it turns out, there’s more to the picture than this. One dimension to it is what Christian theology terms theosis:

Since it is through the possession of happiness that people become happy, and since happiness is in fact divinity, it is clear that it is through the possession of divinity that they become happy. But by the same logic as mean become just through the possession of justice, or wise through the possession of wisdom, so those who possess divinity necessarily become divine. Each happy individual is therefore divine. While only God is so by nature, as many as you like can become so by participation.

So, in addition to the finite, imperfect human being enjoying happiness through contemplating God, goodness and happiness itself — which seems, frankly, a bit lacking in certain respects — the human being also participates in happiness, and presumably knowledge of happiness, in a way involving his or her own transformation, an assimilation to God. Still, how does that happen? Perhaps through that very process of contemplation? Or does it too involve activity of a more practical, less theoretical type? Later on, we learn:

Well, the supreme good is the goal of good men and bad men alike, and the good seek it by means of a natural activity — while the bad strive to acquire the very same thing by means of their various desires, which isn’t a natural method of obtaining the good.

Here, we’ve reached a point where Boethius, having gone on as far as Thomas Aquinas — who tells us that happiness is not any good of the soul, but only God, although happiness is enjoyed through the soul — seems to circle back towards Aristotle, for whom happiness, at least in one of its forms, does consist in a life of virtuous activity.

Now, as we have shown that happiness is the very same good which motivates all activity; so that goodness itself is set as a kind of common reward of human activity. But goodness cannot be removed from those who are good; therefore goodness never fails to receive its appropriate reward.

At least for one who has firmly established the distinctive human kinds of goodness in his or her soul, virtue, this goodness cannot be removed from them as external goods and goods of the body can. But, this differs from Aristotle’s account. Boethius does understand the process of rooting out the vices and cultivating the virtues as a gradual and participational approximation to God.

What we can say then, to tie all these numerous threads back together, is that in Boethius’ work, a dialectical weighing of potential answers to the correlative questions, What is the good for human beings? and What is my good? similar to, complementary with, but differing from those of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, gets carried out.

This raises and resolves likewise the other two questions MacIntyre so rightly regards as interconnected with the first two: How does a person attain the good for human beings?, and more pressingly, with greater particularity, What do I have to do to attain the good for me? Boethius answers that the good ultimately lies in God, but that it can be ours as well, through the path of wisdom, and through the path of virtue, which in the end coincide.

I'm glad to see you bring up Boethius! He was such an influential writer for the middle ages and beyond. I enjoy reading translations of the Consolation of Philosophy to see how different monarchs interpreted his work. Have you ever attended the Kalamazoo Medieval Conference? The International Boethius Society usually has its own session there. I went one year and it's a great time.