About The Four Cardinal Virtues

five clarifications about matters of the virtues people often get wrong

This is a post intended for readers who are interested in ancient or medieval Western philosophy, particularly in the notion of the virtues, but who are a bit confused, in the dark, or perhaps even misinformed about the four that, by convention, we call the “cardinal virtues”. The idea is to provide some useful background, clarification, and reference points that will give those readers a better understanding of what the cardinal virtues are and why they run through multiple philosophical schools and traditions.

One might ask: why write a piece like this now? The answer is pretty simple. I’ve been involved in discussions clarifying these matters for decades, in classes, seminars, talks, comment threads, and even just in offhand conversations. Yesterday, I took part in yet another one, and decided that it was probably time to write something up that I could provide as a useful resource for future conversations. And it might turn out to be helpful even for those who aren’t particularly confused about the virtues, because they haven’t thought much about them at all.

What Are The Cardinal Virtues?

If you look at the vast literature out there that mentions or advocates for what they call “virtues” or “virtue ethics” (much of which isn’t particularly good, unfortunately), you will see quite a few listings of “virtues” that are just dozens of names for qualities generally felt to be positive, provided with no, little, or superficial explanation of why these “virtues” are something people ought to cultivate and act in accordance with.

That is not something radically new. In fact, you can find similar listings in ancient times as well. But typically, these will not be coming from people who have actually devoted any thought to what good traits of character are important, and how we can best understand these and explain them to others. Ancient philosophers, and the medieval thinkers who followed in their course, thought it much more important to think much more coherently about the virtues.

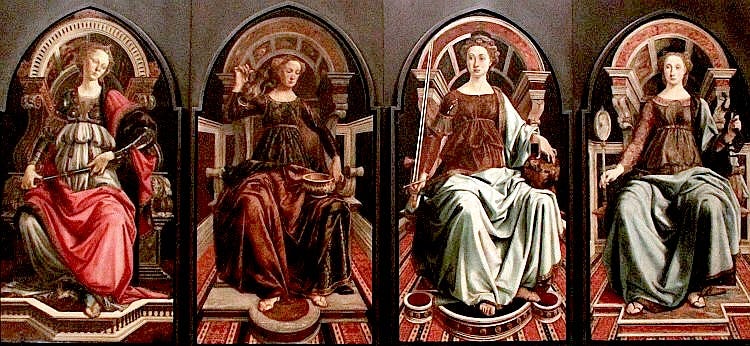

What you’ll find a general agreement about in ancient philosophy (with a few outliers, as we’ll discuss shortly), is on a scheme of four virtues in particular:

Wisdom or Prudence (sophia or phronesis in Greek, sapientia or prudentia in Latin)

Justice (dikaiosunē in Greek, justitia in Latin)

Courage (andreia in Greek, fortitudo in Latin)

Temperance (sophrosunē in Greek, moderatio or temperantia in Latin)

If you read classic literature, you’ll sometimes find other Greek or Latin terms being used as well. And in English translation, you’ll find ranges of terms being employed as well to convey these key character traits. For example, you’ll find some people using “fortitude” instead of “courage” (perhaps because they like the Latinate, old-fashioned sound of it better). Alternately, they might speak of “bravery. But all three of these terms, unless someone specifies in advance that they signify something distinct (to them, not to all of us), really mean the same thing, and designate the same virtue.

Whose Virtues Are These?

Among the people who mistakenly think that these four cardinal virtues belong primarily to one philosophical school, tradition, or movement, in my experience they tend to associate them either with Platonic, Stoic or Christian philosophy. If you’ve been introduced to Stoicism and you’ve learned that the Stoics advocate developing four cardinal virtues, you can be quite surprised to find Plato talking about those same four virtues in his works, or by later Christian thinkers like Augustine referencing them in their texts.

As it so happens, most of the main schools or figures of ancient Western philosophy that had any sort of well-articulated ethics turn out to use the schema of the four cardinal virtues. While there are a few other virtues (magnanimity and piety, for example) mentioned in Plato’s dialogues, wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance are the four you will most often see discussed, and the framework set out in Republic book 4 ends up being pretty determinative for the long and varied Platonist tradition.

What about the Stoics? They too use this fourfold classification, but let’s hold on a little bit, because the Stoics arrive a bit late on the scene, after several other important schools are underway. It turns out that the Cynic literature and testimonials, at least what we have of it, also discusses and recommends these virtues. One might say that confluence reflects a common Socratic teaching that goes down different paths through Plato and Antisthenes, but the fact that Epicurus and his followers, a decidedly non-Socratic-derived school, also frames their hedonistic ethics using these four virtues goes against that idea.

By the time Zeno is developing his new approach in philosophy, not only are these other schools already on the scene, but Zeno himself has studied with representatives of some of them (Crates the Cynic, Polemo the Platonist, as well as Stilpo the Megarian). The Stoics take up this by-then common schema of the four cardinal virtues and provide their own reinterpretations of it in their philosophical system. Eclectics like Cicero will also adopt this fourfold understanding of the virtues.

When later Christian (as well as Jewish, e.g. Philo of Alexandria) thinkers, generally with a good understanding of ancient pagan philosophy, are developing their ideas within a new, rich, religious framework, they will generally do so through some engagement with neo-Platonist thought, which by that time isn’t strictly Plationic but incorporates a good bit of Aristotelian and Stoic ideas and practices into its matrix. Generally, Christian intellectuals in antiquity had a solid background in, and could critically respond to, reject, or incorporate ideas and arguments coming from all the major ancient schools.

So whose four cardinal virtues are they? Pretty much anyone in ancient philosophy who wanted to use them and who developed thoughtful, coherent accounts of them articulated in their works. It is only when we start getting into the different understandings of them worked out by these schools that we can call them distinctively “Platonic”, or “Stoic”, or “Christian”.

Aristotle And Other Outliers

You will no doubt have noticed that there is one major school of ancient philosophy that we haven’t discussed yet, and that is of Aristotle and his followers, what we sometimes call the “Peripatetic” school (given that epithet because apparently Aristotle walked around as he taught in the Lyceum). Don’t Aristotelians also recognize the four cardinal virtues?

As a site-note, this is a matter where people who claim to be Thomists, that is, followers of Thomas Aquinas, will often get themselves mixed up. And I’m not talking about people who actually read Thomas’ works in the spirit they’re intended, and perhaps even also read some of the many people whose works he incorporates into his own, but rather about people who are on “team Thomas” so to speak.

They know that Thomas talks about the four cardinal virtues (as well as the three theological ones), and they know that Thomas is an Aristotelian (which is mostly true), and maybe they even read a few passages where Thomas shoehorns Aristotle’s account of the virtues into a four cardinal virtue schema. And since they don’t actually study Aristotle (except perhaps with Thomistoid blinders on), they assume Aristotle must have bought into the cardinal virtues as well.

All you have to do is read the Nicomachean Ethics books attentively to realize that is not the case. Aristotle does discuss justice, courage, and temperance as moral virtues, and prudence as an intellectual virtue (albeit one intimately connected with the moral virtues). But he also identifies and analyses eight other virtues which he regards as distinct from the other four: good temper, generosity, magnificence, right ambition, magnanimity, truthfulness, friendliness, and good humor. So in place of four, he offers us many more.

There’s a different sort of outlier when it comes to the virtues, namely thinkers and schools who don’t think that four is too few when it comes to the virtue, but instead that four are too many. Those would be thinkers who regard virtue as something that is singular. These aren’t by the way thinkers, like the Stoics, who say that technically there’s one virtue and it takes on four main modalities, the ones we call the cardinal virtues. These are people who say even that is a mistake. There weren’t a lot of them, but they do seem to have included the minor Socratic schools of Megarians and Elian-Eretrians.

So long story short, not everyone accepts the schema of four cardinal virtues in ancient Western philosophy. But the vast majority of them do.

What About Other Virtues That Are Left Out?

Without necessarily endorsing Aristotle’s theory of the virtues, a person might want to argue against the many different schools and thinkers who do stick with the cardinal virtues. And a prime reason would be the concern that by reducing the character traits a human being needs in order to flourish and to be a good person to just those four, other morally important traits are left out as well. Let’s take just a few examples:

A very common concern newcomers bring up when it comes to Stoic ethics is that kindness or compassion get left out. That does seem to be a real worry, until of course, we read actual Stoic texts discussing ethics, and we find out that kindness and compassion (the latter in the sense of behaving compassionately, not so much in terms of affect) actually full under the virtue of justice, as one of its main parts. So they didn’t leave it out at all.

Not-so-careful readers of Plato’s Republic might look at his treatment of the cardinal virtues in book 4 and wonder where truthfulness or honesty comes in. As it so happens, that’s one of the aspects of justice, mentioned in terms of its opposite, lying, which is one determinate kind of injustice.

What about frugality, that is managing one’s money and possessions wisely? Well, not only is that a part of the virtue of temperance, Cicero even is willing to call temperance by that name, and perhaps extend it to all of the virtues.

What about perseverance in sticking with a commitment one has made? The Stoics at least (I have to check whether later Platonists also take this tack) place that as a sub-virtue under that of courage.

That isn’t to say that there aren’t some other virtues recognized down the line that won’t be as easily addressed by assimilating them into the scope of the four cardinal virtues. When we get into the Christian era, virtues like humility, love, faith and the like stand out as contributing something distinctive. But for many of the objections contemporary people might raise, they’ll usually find them already addressed to their satisfaction by the texts that we have.

Different Schools’ Understandings Of The Cardinal Virtues

At this point, we have clarified a few key matters about the cardinal virtues that people sometimes get confused about:

what the four cardinal virtues are

which ancient philosophical schools use that schema in their virtue ethics

which ancient philosophical schools don’t use that schema

how objections that virtues have been left out get addressed

There is one last point that we need to clear up as well, since it easily gives rise to misunderstandings. It would be easy for someone to see that Platonists, Epicureans, Stoics, and Christian thinkers all write about wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance, and then to conclude that, since they’re all using the same term, they’re all advocating for the same thing. And that would be because they all think that those terms mean precisely the same dispositions of the soul, the same set of virtues.

That’s definitely not the case, as we can see if we take the Epicureans and Christian thinkers and compare them with Stoics and Platonists. The Epicureans value the virtues, but they do so instrumentally, not because those virtues are something good in themselves. Instead for them, it is because we human beings need those virtues in order to have as happy a life as possible, that is, as pleasant and pain-free a life as possible. Epicureans clearly have a very different conception of what these four virtues involve than do Platonists, Stoics, and most Christians.

Christian thought from antiquity and the middle ages covers a vast range of thinkers and interpretations, and they are far from all being in agreement with each other. So let’s just take one important early thinker, St Augustine of Hippo. He is fairly strongly influenced by and appreciative of the later Platonism of his time, and also thinks that the Stoics, while wrong about some matters, have others right. He advocates for the same four cardinal virtues as they do. But will the possession of those virtues by themselves make us happy? They’ll certainly contribute to it, but something greater than those is needed, and that is what he thinks Christian thought, practice, and life will provide.

Even the Stoics and the Platonists aren’t in complete agreement about the nature of the virtues, not least because the two schools have different moral psychologies and metaphysics. If we look carefully at the Stoic authors we possess, we won’t actually find their treatments of the subordinate virtues under each cardinal virtue perfectly mapping onto each other.

So it’s important not to mistakenly assume that any philosophers who use the four cardinal virtues arrangement in their ethics are all on the same proverbial page. You have to study the texts and thinkers for each tradition independently of each other, without projecting similarities of conceptions and systems onto them just on the basis of shared moral vocabulary.

So, that’s it on this topic for now! For some of you, reading this, your reaction is perhaps “Duh! We all know that.” If that’s the case, well thanks for reading this far, because you didn’t really need it. But if you’re learned something useful along the way here, then you are precisely who this article was intended for!

Thank you Dr. Sadler! Once again, very interesting. I had no idea that the four cardinal virtues were present in more than one philosophy. Without a doubt, I gained new knowledge today.

Thanks for a great read with my coffee this morning.