10 Definitely Fake Quotes Not From Plato

Plato didn’t say any of these, but I can tell you (in most cases) who did!

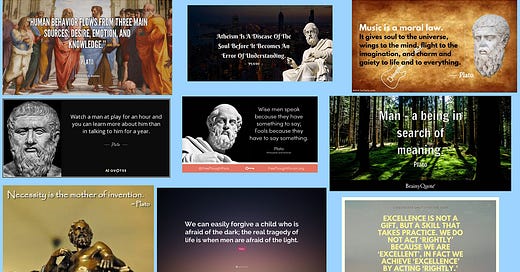

Some time back, I produced a video identifying ten or eleven fake quotes wrongly attributed to Aristotle. Then I polled my viewers, readers, and subscribers about what philosopher I should focus on next. Plato was the overwhelming favorite. So I created a second “fake quotes” callout video, specifically focused on Plato, picking out ten commonly misattributed short passages.

I won’t go over the reasons why people produce, post, and repost fake quotes here. And I’ll simply take it for granted that, even if one thinks there’s some “truth” or usefulness to those misattributed passages, it is nevertheless bad in multiple senses to take fake quotes as real, as well as to post them as if they were genuine. Those involve larger and more complex topics, and I intend to do some additional writing specifically exploring these issues.

The ten fake quotes I selected misattributed to Plato are just the tip of a vast iceberg, but they are among those that pop up often on quote sites, in social media, in blog posts, in videos, and unfortunately even in published but not adequately fact-checked books.

Here’s the first set of fake quotes wrongly attributed to Plato

Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle

Watch a man at play for an hour and you can learn more about him than in talking to him for a year.

Wise men talk because they have something to say; fools, because they would like to say something

We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light

Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, gaiety and life to everything.

Man is a being in search of meaning

Atheism is a disease of the soul, before it becomes an error of the understanding

Excellence is not a gift, but a skill that takes practice. We do not act rightly because we are excellent, in fact, we achieve excellence by acting rightly

Necessity is the mother of invention

Human behavior flows from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge

And here’s the video discussing each of these.

There’s a bit to say about each of these. When it comes numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 8, we can actually identify where the passage originates. In most of these cases, the passage is of recent provenance.

#1 comes from Ian Maclaren’s 1897 Christmas message, which has slightly different wording: “Be pitiful, for every man is fighting a hard battle.” It then gets misattributed to Plato by the recent author Dan Millman in a 1992 book, No Ordinary Moments: A Peaceful Warrior’s Guide to Daily Life.

#2 dates from a much earlier era. Richard Lindgard in his 1671 Letter of Advice to a Young Gentleman Leaving the University Concerning His Behaviour and Conversation in the World. He writes: “If you would read a man’s Disposition, see him Game; you will then learn more of him in one hour, than in seven Years Conversation, and little Wagers will try him as soon as great Stakes, for then he is off his Guard.” Again, a late modern author takes this passage, and then misattributes it to Plato, in this case Alan Loy McGinnis in his 1987 Confidence : How to Succeed at Being Yourself.

#3 does not derive from any of Plato’s writings. It’s pure fabrication, but it does show up in two works that wrongly attribute it to Plato. The first is Abram N. Coleman’s 1903 book Proverbial Wisdom: Proverbs, Maxims and Ethical Sentences, of Interest to All Classes of Men. The second instance is Tryon Edwards’ 1908 A Dictionary of Thoughts: Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, Both Ancient and Modern.

#5 is from page 120 of John Lubbock’s 1889 book The Pleasures of Life, Part II. Not remotely by Plato, and it remains unclear who originally misattributed this passage to the ancient philosopher.

#6 comes from Abraham Joshua Heschel’s 1954 book, The Insecurity of Freedom, in which he is at least discussing Platonic dialogues and the character of Socrates. But it is Heschel’s own late-modern reinterpretation of what Plato and Socrates were about. The passage then gets conflated with what Plato himself supposedly says somewhere, but in actually never says, in his texts.

#7 provides another interesting example. In this case, the passages derives from William Fleming, who claimed to find it in Plato’s Laws (where you won’t find it). It then shows up in Samuel Austin Allibone’s Prose Quotations from Socrates to Macaulay, and then gets uncritically but predictably picked up by the website Conservapedia.

#8 is from one of the all-too-common sources of fake quotes, William Durant’s ever-popular, sometimes-accurate, best-seller 1926 book The Story of Philosophy. This passage interestingly enough doesn’t come from his discussions of Plato, but rather Aristotle. So, it’s not just a garbled modern interpretation treated as if it’s actually coming from an ancient author’s text. It’s the wrong author

Numbers 4, 9, and 10 at least in some respect derive in part from ancient authors.

#4 doesn’t jibe with any passage in Plato’s works. It might come from the Stoic philosopher Seneca, who at one point quotes the earlier Epicurean poet and philosopher Lucretius as saying “we are as much afraid in the light as children in the dark, paraphrasing a longer passage from On the Nature of Things.

#9 does come from Plato . . . kinda sorta, but not really. Benjamin Jowett’s popular and periphrastic 1871 translation of Plato’s Republic includes the line: “The true creator is necessity, who is the mother of our invention.” This is Jowett taking considerable liberties with the text, as his alternate and more faithful translation, “our need will be the real creator,” indicates.

Finally, #10 is a formulation that is at least reliably Platonic, since it references the three parts of the soul detailed in Platonic anthropology. But this formulation is nowhere to be found in Plato’s texts, which for any reader of Plato is not a surprise, since he doesn’t use a late modern term like “human behavior”. It also reads like a gloss from someone who has read Plato in translation, and doesn’t know the original Greek terms, since thumos is being dubiously translated as “emotion”, and the plural epithumiai as “desire”

So there you have it, or rather them — passages that you know aren’t from Plato. You probably ought to be on your guard with anyone who uses them and misattributes them to Plato, especially if — when they’ve had their error pointed out to them — they double down and try to claim that either they are by Plato, or that despite being fake quotes they’re still “true” in some manner.

I’ll be researching and creating more of these videos and posts calling out fake quotes by famous philosophers. Feel free to comment which philosopher you think I ought to tackle next! (But you may want to check this resource page out first)

Gregory Sadler is the president of ReasonIO, a speaker, writer, and producer of popular YouTube videos on philosophy. He is co-host of the radio show Wisdom for Life, and producer of the Sadler’s Lectures podcast. You can request short personalized videos at his Cameo page. If you’d like to take online classes with him, check out the Study With Sadler Academy.